Help us improve in just 2 minutes—share your thoughts in our reader survey.

López v. Gonzales

| |

| López v. Gonzales | |

| Docket number: 05-547 | |

| Court: United States Supreme Court | |

| Court membership | |

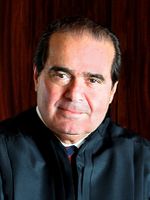

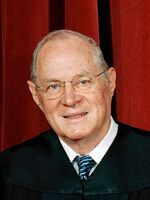

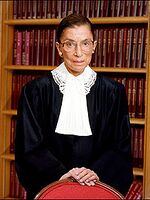

| Chief Justice John Roberts Associate Justices John Paul Stevens • Antonin Scalia • Anthony M. Kennedy • David Souter • Clarence Thomas • Ruth Bader Ginsburg • Steven G. Breyer • Samuel Alito | |

López v. Gonzales is a United States Supreme Court case that was decided on December 5, 2006. The case concerned the application of criminal charges in deportation proceedings and whether a crime considered a felony under state law but a misdemeanor under federal law constitutes an aggravated felony and is grounds for removal under federal immigration law.

In an 8-1 ruling, the Court reversed the judgment of the United States Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit and remanded the case for further proceedings, holding that "conduct made a felony under state law but a misdemeanor under the Controlled Substances Act (CSA) is not a “felony punishable under the Controlled Substances Act” for Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) purposes."[1] Justice David Souter wrote the majority opinion. Justice Clarence Thomas wrote a dissenting opinion.[1]

Background

In 1997, Jose López, a lawful permanent resident living in South Dakota, was arrested for and pleaded guilty to charges under state law of aiding and abetting another person's cocaine possession. South Dakota law treated the conviction as a felony. On the grounds that this amounted to an aggravated felony under the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA), the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) began legal proceedings to deport López. Under the INA, an aggravated felony includes illicit drug trafficking, which Title 18 of the United States Code defines to include "any felony punishable under the Controlled Substances Act." INS argued that state felonies fell under felonies punishable by the Controlled Substances Act (CSA).[1][2][3]

López filed for a cancellation of his deportation, arguing that the federal Controlled Substances Act treated his crime—aiding another person's possession of an illicit substance—as a misdemeanor rather than a felony. The immigration judge for the case denied the cancellation request, ruling that because the crime was a felony under state law, it counted as an aggravated felony under the INA at the federal level.[1][2]

On appeal, the Board of Immigration Appeals affirmed. López filed suit against the attorney general at the time, Alberto Gonzales, and brought the case to the United States Court of Appeals for the 8th Circuit. The Eighth Circuit affirmed the ruling of the lower courts that a state felony crime amounts to an aggravated felony under the INA.[1][2]

López appealed to the United States Supreme Court, which agreed to hear the case on April 3, 2006.[2]

Question presented

The court limited oral arguments to the following question:[4]

|

Outcome

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

On December 5, 2006, the Court reversed the judgment of the United States Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit and remanded the case for further proceedings, holding that "conduct made a felony under state law but a misdemeanor under the Controlled Substances Act (CSA) is not a “felony punishable under the Controlled Substances Act” for Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) purposes."[1] Justice David Souter wrote the 8-1 majority opinion. Justice Clarence Thomas wrote the sole dissenting opinion.[1]

Opinion

In the Court's majority opinion, Justice David Souter wrote:[1]

| “ | Finally, the Government’s reading would render the law of alien removal, see 8 U. S. C. §1229b(a)(3), and the law of sentencing for illegal entry into the country, see USSG §2L1.2, dependent on varying state criminal classifications even when Congress has apparently pegged the immigration statutes to the classifications Congress itself chose. It may not be all that remarkable that federal consequences of state crimes will vary according to state severity classification when Congress describes an aggravated felony in generic terms, without express reference to the definition of a crime in a federal statute (as in the case of “illicit trafficking in a controlled substance”). But it would have been passing strange for Congress to intend any such result when a state criminal classification is at odds with a federal provision that the INA expressly provides as a specific example of an “aggravated felony” (like the §924(c)(2) definition of “drug trafficking crime”). We cannot imagine that Congress took the trouble to incorporate its own statutory scheme of felonies and misdemeanors if it meant courts to ignore it whenever a State chose to punish a given act more heavily. ... In sum, we hold that a state offense constitutes a “felony punishable under the Controlled Substances Act” only if it proscribes conduct punishable as a felony under that federal law. The judgment of the Court of Appeals is reversed, and the case is remanded for further proceedings consistent with this opinion.[5] |

” |

| —Justice David Souter | ||

Dissenting opinion

|

|

In his dissent, Justice Clarence Thomas wrote:[1]

| “ | Jose Antonio Lopez pleaded guilty to aiding and abetting the possession of cocaine, a felony under South Dakota law. The Court holds that Lopez’s conviction does not constitute an “aggravated felony” because federal law would classify Lopez’s possession offense as a misdemeanor. I respectfully dissent. Lopez’s state felony offense qualifies as a “drug trafficking crime” as defined in §924(c)(2). A plain reading of this definition identifies two elements: First, the offense must be a felony; second, the offense must be capable of punishment under the Controlled Substances Act (CSA). No one disputes that South Dakota punishes Lopez’s crime as a felony. See S. D. Codified Laws §22–42–5 (1988). Likewise, no one disputes that the offense was capable of punishment under the CSA. See 21 U. S. C. §844(a). Lopez’s possession offense therefore satisfies both elements, and the inquiry should end there. The Court, however, takes the inquiry further by reasoning that only federal felonies qualify as drug trafficking crimes. According to the Court, the definition of drug trafficking crime contains an implied limitation: “any felony punishable [as a felony] under the” CSA. The text does not support this interpretation. Most obviously, the language “as a felony” appears nowhere in §924(c)(2). Without doubt, Congress could have written the definition with this limitation, but it did not. ... The Court’s approach is unpersuasive. At the outset of its analysis, the Court avers that it must look to the ordinary meaning of “illicit trafficking” because “the statutes in play do not define the term.” Ante, at 5. That statement is incorrect. Section 1101(a)(43)(B) of Title 8 clearly defines “illicit trafficking in a controlled substance,” at least in part, as “a drug trafficking crime (as defined in section 924(c) of title 18).” (Emphasis added.) Therefore, whatever else “illicit trafficking” might mean, it must include anything defined as a “drug trafficking crime” in §924(c)(2). Rather than grappling with this definition of the relevant term, the Court instead sets up a conflicting strawman definition. In fact, it is the Court’s interpretation that will have a significant effect on removal proceedings involving state possession offenses. Federal law treats possession of large quantities of controlled substances as felonious possession with intent to distribute. States frequently treat the same conduct as simple possession offenses, which would escape classification as aggravated felonies under the Court’s interpretation. Thus, the Court’s interpretation will result in a large disparity between the treatment of federal and state convictions for possession of large amounts of drugs. And it is difficult to see why Congress would “authorize a State to overrule its judgment” about possession of large quantities of drugs any more than it would about other possession offenses. Ante, at 11. Finally, the Court admits that its reading will subject an alien defendant convicted of a state misdemeanor to deportation if his conduct was punishable as a felony under the CSA. Accordingly, even if never convicted of an actual felony, an alien defendant becomes eligible for deportation based on a hypothetical federal prosecution. It is at least anomalous, if not inconsistent, that an actual misdemeanor may be considered an “aggravated felony.” Because a plain reading of the statute would avoid the ambiguities and anomalies created by today’s majority opinion, I respectfully dissent.[5] |

” |

| —Justice Clarence Thomas | ||

See also

External links

- Search Google News for this topic

- López v. Gonzales (2006)

- Oyez case file for López v. Gonzales (2006)

Footnotes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 U.S. Supreme Court, López v. Gonzales, decided December 5, 2006

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Oyez, "López v. Gonzales," accessed June 9, 2025

- ↑ In 2003, the Immigration and Naturalization Service was divided into three agencies: U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, and U.S. Customs and Border Protection.

- ↑ Supreme Court of the United States, "05-547 LOPEZ V. GONZALES - Questions Presented," archived June 7, 2010

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Note: This text is quoted verbatim from the original source. Any inconsistencies are attributable to the original source.