City of Berkeley Redistricting Map Referendum, Measure S (November 2014)

| Voting on Redistricting Measures | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Ballot Measures | |||

| By state | |||

| By year | |||

| Not on ballot | |||

|

A City of Berkeley Redistricting Map Referendum was on the November 4, 2014 election ballot for voters in the city of Berkeley in Alameda County, California. It was approved, thereby upholding the controversial redistricting law that petitioners had sought to repeal.

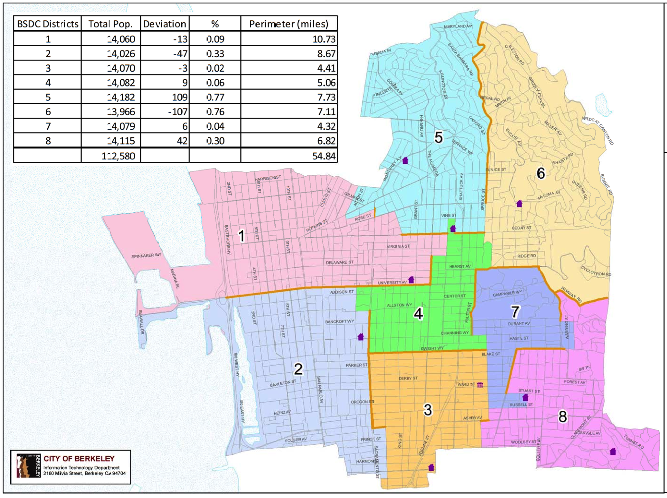

In December 2013, the Berkeley city council adopted a new redistricting map ordinance, known as the Berkeley Student District Campaign map, which included the student-majority District 7 near Telegraph Avenue. This map concentrated most of District 7 on the south side of the college campus. According to critics, this resulted in a district more dominated by conservative students because the map excluded student co-ops and dorms on the north side of campus, which are perceived as progressive, and added fraternities and sororities on the south side of campus, which are considered more conservative.[1][2]

When the city council voted six to three to accept the ordinancne with the new redistricting map, including the controversial District 7 boundaries, a group called the Berkeley Referendum Coalition began a petition drive to force a referendum on the redistricting ordinance, and, on January 21, 2014, they turned in 7,867 signatures to the Berkeley City Clerk. After a random sampling of the signatures, the Alameda County Registrar of Voters concluded that the petitions contained valid signatures numbering well over the 5,275 required to force a referendum if the city council did not itself rescind its ordinance. The city council voted to put the map before voters in November.[3][4][5]

Despite the fact that the controversial redistricting map was targeted by a successful veto referendum petition and might have been rejected by a vote of the people in November, the courts decided that this new map would be used during the November 2014 city council elections. Thus, in the same election where voters were deciding not to approve the redistricting ordinance, they were also voting in accordance with it. Many critics believed this to be an obviously unfair way to conduct the election, proposing that the judge in the court case should have forced the city to use a less contentious map until the map targeted by Measure S could be approved or rejected by voters. They proposed that the targeted map would give an advantage to a conservative candidate in District 7, potentially replacing Councilmember Kriss Worthington. If this happened and if the voters rejected Measure S, it could have resulted in a candidate serving on the council for four years and having an incumbent advantage in the next election largely due to a redistricting map that had been rejected by voters.[6]

A "yes" vote supported the city council members and approved the proposed map. A "no" vote would have rescinded the map.

Election results

| City of Berkeley, Measure S | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Result | Votes | Percentage | ||

| 21,240 | 63.81% | |||

| No | 12,048 | 36.19% | ||

Election results via: Alameda County Registrar of Voters

Text of measure

Ballot question

The question on the ballot:[7]

| “ |

Shall Ordinance No. 7,320-N.S. authorizing the adjustment of Berkeley City Council district boundaries pursuant to Section 9, Article V of the Berkeley City Charter, to equalize population in the districts as a result of population changes reflected in the 2010 decennial federal census be adopted?[8] |

” |

Impartial analysis

The following impartial analysis of Measure S was provided by the office of the city attorney:[7]

| “ |

The City Charter divides the City of Berkeley into 8 council districts, with the Mayor elected at large. The City Charter requires the City Council to adopt new council districts every ten years, based on the decennial census, and requires the Council to complete its redistricting process no later than the end of the third year after the census is taken. The Charter requires that council districts be as nearly equal in population as may be. Based on the 2010 census, districts of equal population would each have 14,073 residents. The existing districts, which were based on the 2000 census, diverge from this population by a minimum of 4.5% and a maximum of 18%. Until 2012, the Charter required that new council district boundaries preserve to the extent possible the original council district boundaries established by a charter amendment in 1986. In 2012, after considering a number of proposed redistricting maps, the Council placed a charter amendment on the ballot to eliminate the requirement that new districts conform as closely as possible to the 1986 boundaries. The voters adopted this amendment in November 2012. In 2013 the Council reinitiated the redistricting process under the revised Charter rules. In December 2013, after considering a total of 7 redistricting proposals, the Council adopted an ordinance establishing new council district boundaries with a maximum population deviation between district size and equal population of 0.77%. Under the City Charter and state law, voters may place an ordinance adopted by the Council on the ballot for voter approval or rejection by collecting the signatures of registered voters equal to 10% of the entire vote cast for all candidates for Mayor at the last preceding election at which a Mayor was elected. An ordinance that is placed on the ballot in this manner goes into effect if it is approved by a majority of the voters voting on it. This measure was placed on the ballot as the result of a petition signed by voters. A "yes" vote would approve the redistricting ordinance adopted by the Council, in which case it would go into effect. A "no" vote would reject the redistricting ordinance adopted by the Council, requiring the Council to adopt a new redistricting ordinance and leaving in place the existing districts that were adopted in 2002 until it does so.[8] |

” |

| —Zach Cowan, Berkeley City Attorney[7] | ||

Full text

The full text of the redistricting ordinance is available here.

Support

Supporters

Eric Panzer, a Berkeley resident, wrote an opinion piece in support of the redistricting map.[9]

The following individuals signed the official arguments in support of Measure S:[7]

- State Senator Loni Hancock (D-9)

- Assemblymember Nancy Skinner (D-15)

- Tom Bates, Berkeley Mayor

- Pavan Upadhyayula, ASUC President

- Safeena Mecklai, ASUC External Affairs Vice President 2013-2014

Council members

The following council members voted to approve the Berkeley Student District Campaign map:[10]

- Mayor Tom Bates

- Councilwoman Linda Maio (District 1)

- Councilman Darryl Moore (District 2)

- Councilwoman Laurie Capitelli (District 5)

- Councilwoman Susan Wengraf (District 6)

- Councilman Gordon Wozniak (District 8)

Arguments in favor

Eric Panzer, a member of several Berkeley city commissions, published an op-ed supporting the district map and opposing the referendum attempt to overturn it. He wrote:[9]

| “ |

This referendum campaign represents an effort to short-circuit the community redistricting process and delay implementation of new City Council districts. The main impetus for this referendum is Councilmember Kriss Worthington’s support for an eleventh-hour redistricting proposal that was crafted within his own council office. Redistricting proposals were due to the City Clerk by March 15, 2013, but Worthington’s proposal was not introduced until Sept. 10, nearly six months later. Supporters of that map evaded the public scrutiny of the formal submission process and are now threatening to drag redistricting beyond the Charter-mandated three-year deadline for its completion. This needless referendum would also waste your money. Despite the 17 community meetings, public hearings, and Council meetings between 2011 and 2013, referendum supporters are claiming that the Council-approved map was chosen without community input. If their referendum goes to the ballot, Berkeley will need to call an otherwise-unnecessary special election that will cost a quarter-million dollars of your money. Moreover, putting this referendum on the ballot would likely mean that the 2014 election would be conducted with the now-outdated and imbalanced districts adopted in 2000, a clear violation of the principle of “one person, one vote.”[8] |

” |

| —Eric Panzer[9] | ||

Official arguments

The following was submitted as the official arguments in favor of Measure S:[7]

| “ |

“Redistricting” is the redrawing of Berkeley’s Council district boundaries. To protect equal representation, federal law requires that populations across districts be rebalanced every 10 years following each national Census. Voting YES on Measure S supports citizen participation. Berkeley citizens were encouraged to submit their own map proposals. The City Council considered a total of seven (7) maps drawn by Berkeley residents. The City Council and the League of Women Voters held seventeen (17) forums, community meetings, and public hearings on redistricting. In the end, the Council adopted a map drawn by Berkeley citizens. Voting YES on Measure S protects communities of interest. The City Council chose a map that met all the criteria in the Berkeley City Charter: populations are rebalanced across all districts, district boundaries are compact and easy to understand, communities of interest are protected, and no incumbent has been drawn out of his/her district. This map meets all federal, state, and local rules for redistricting. This map is the only map whose use has been affirmed by the courts. Voting YES on Measure S allows Berkeley to move on and saves taxpayers’ money. We have been working on our redistricting process for over three years. Without your YES vote, Berkeley will need to spend additional years and tens of thousands more dollars to redo redistricting for the third time in just four years. Voting Yes on Measure S ensures equal representation and supports a vote for fair districts. The new map's population deviation is less than 1 percent and the City Council approved these Charter-compliant districts with a supermajority vote (6 "yes" votes to 3 "no" votes). Vote YES on Measure S to approved the redistricting map and keep Berkeley City Council districts fair.[8] |

” |

| —State Senator Loni Hancock (D-9), Assemblymember Nancy Skinner (D-15), Mayor Tom Bates, Pavan Upadhyayula and Safeena Mecklai[7] | ||

Opposition

Opponents

The Berkeley Referendum Coalition was the group behind the referendum and the group that paid for referendum signatures to be collected. This group was hoping voters would reject the redistricting map at the November election.

- Lisa Stephens, the chair of the Berkeley Rent Stabilization Board

- Nancy Carleton, a former chair of the Zoning Adjustments Board

- David Blake, a member of the Rent Stabilization Board

- James Marshall, a computer programmer who founded the Berkeley Institute for Free Speech Online

- Gene Poschman, a planning commissioner

- Daniel Knapp, the owner of Urban Ore

- Martin Spence, a legal assistant at Cooper White & Cooper

- Sara Shumer, former member of the Berkeley Zoning Adjustments Board

- Urban Ore

The following individuals signed the official arguments against Measure S:[7]

- Nigel Guest, president of the Council of Neighborhood Associations

- Shirley Dean, signing on behalf of Berkeley Neighborhoods Council

- Viveka Jagadeesan, UC Berkeley Student and co-president of Berkeley Common Cause

- Spencer Hitchcock, Berkeley Student Cooperative President

- Mansour Id-Deen, president of Berkeley NAACP

Council members

The following council members voted against implementing the Berkeley Student District Campaign map:[10]

- Councilman Kriss Worthington (District 7)

- Councilman Jesse Arreguín (District 4)

- Councilman Max Anderson (District 3)

Arguments against

Councilman Worthington and his supporters described the council redistricting map as a way to dilute the progressive voice of the city.[2]

The referendum effort to repeal the ordinance was supported by the progressives of the city, who argued that the council-approved redistricting map was a way to remove Councilman Kriss Worthington (District 7) from the council by forming his district around conservative portions of campus, while excluding more liberal dorms and student co-ops.[11]

Councilman Jesse Arreguín (District 4) said, "It’s amazing that this would happen in Berkeley, that we would have a Texas-style gerrymandering. The good thing about this campaign is that we were able to talk to the community about what was going on.”[12]

Official arguments

The following was submitted as the official arguments in opposition to Measure S:[7]

| “ |

Vote NO on S. Reject Council's gerrymander that has disenfranchised voters, protects incumbents and divides neighborhoods and communities of interest, and empower a Citizens’ Independent Redistricting Commission to draw fair lines once and for all. Redistricting in Berkeley has become a sordid saga stuck on repeat. Every ten years, boundaries are manipulated for political gain, protecting select incumbents and punishing political enemies to the detriment of neighborhoods and communities of interests. But this time, the decennial debacle has gotten worse with Council breaking laws to impact certain Council races. In 2012, Council delayed redistricting under the guise of creating a Student District; conveniently, certain Councilmembers benefited from unchanged districts in their election races that year, disenfranchising over 4,300 voters from electing their Councilmember for 6 years. After Council was granted unprecedented control, a “community” process was initiated where 4 of 7 maps were submitted by the same group of insiders, stacking the deck in favor of their controversial gerrymander. The gerrymander unnecessarily divided neighborhoods, such as Halcyon, West Berkeley and LeConte, and split students to create a Fraternity-dominated District. All other maps were not considered -it was fait accompli from the beginning. Subsequently, neighbors, students and community leaders successfully gathered 7,867 signatures to compel Council to make things right. But rather than do its job, Council chose to violate the Charter and open government laws to punt its gerrymander on the ballot and then absurdly sued themselves and community members with taxpayer money. You’re now asked to approve a map that Council has already imposed through a series of egregious misdeeds. It’s a conflict of interest when we allow politicians to draw their lines, cherry-picking winners and losers. BREAK THE CYCLE: Reject Council’s gerrymander and let a Citizens' Redistricting Commission create a fair map. VOTE NO ON S.[8] |

” |

| —Nigel Guest, Shirley Dean, Viveka Jagadeesan, Spencer Hitchcock and Mansour Id-Deen[7] | ||

Campaign finance

The Berkeley Coalition Referendum paid the Bay Area Petitions of Santa Cruz $5,000 to help collect the necessary signatures to put the referendum on the ballot. As of February 3, 2014, the Coalition had only raised $2,790 of that $5,000 in contributions. Michael O'Malley, who co-owns the Daily Planet, was the largest contributor, giving $1,000 to the referendum effort. According to reports, the Berkeley Coalition Referendum was searching for donations to pay off $5,000 to $6,000 of debt it had accrued from paying Bay Area Petitions of Santa Cruz, printing support materials and organizing events.[11][12]

Donations as of February 3, 2014, included:[11][10]

| Donor | Amount |

|---|---|

| Michael O'Malley | $1,000 |

| Gene Poschman | $300 |

| Martin Spence | $250 |

| Sara Shumer | $200 |

| Urban Ore | $300 |

| James Marshall | $200 |

| Lisa Stephens | $100 |

| Nancy Carleton | $100 |

| David Blake | $100 |

| Daniel Knapp | $100 |

| Donations under $100 each | $140 |

| TOTAL | $2,790 |

The redistricting map

The redistricting map approved by the council excluded from District 7 certain student co-ops and dorms on the north side of campus, which were perceived as progressive, and added fraternities and sororities on the south side of campus, which were considered to be more conservative.[1]

Below is the redistricting map that was approved by the council and put on hold after the successful referendum effort:

Alternative map

An intern in Worthington’s office named Stefan Elgstrand drew up an alternative redistricting map, called the United Student District Amendment (USDA), which included parts of the north side of campus in District 7 boundaries, with fewer blocks included in the south of campus. This map was proposed to the city council as an alternative, but the city council voted six to three to approve the original map above.[2]

The proposed alternative map is displayed below:

Background

November district map lawsuit

Because the city council put off the election for this referendum until November, the question arose: what district map would be used in the November 4, 2014, election before voters could decide to approve or reject the council's map? A lawsuit, City of Berkeley v. Tim Dupuis and Mark Numainville, was filed to determine the answer. Opponents of the redistricting map argued that the map should not be used because the successful petition drive should result in the suspension of the map until voters decide on it. The question was decided by Alameda County Superior Court Judge Evelio Grillo, who decided in favor of the city, allowing the redistricting map targeted by the referendum to be used in the November election, instead of alternative maps that were proposed. The ruling stated that the council-approved map “is the one that best complies with meeting the mandates of equal protection and minimizing any disruption to the election process.”[6]

Councilman Jesse Arreguín wrote, “Obviously I am disappointed. I hoped that the judge would have given more consideration to the several alternate maps submitted which were constitutionally compliant and complied with the City Charter, rather than entering the political thicket and picking a map that was stayed by a successful citizens referendum [sic]." Arreguin also said, “This ruling sets a terrible precedent and encourages cities to purposely time their action on a referendum so as to inoculate it from challenges and renders the citizens right [sic] to a referendum as a futile exercise of democracy and makes a referendum essentially meaningless.”[6]

Measure R

In 2012, Berkeley city voters approved Measure R, which allowed city redistricting to be done through city council ordinance, provided the proposed districts "be as equal in population as feasible taking into consideration topography, geography, cohesiveness, contiguity, integrity, compactness of territory and communities interest, and have easily understood boundaries such as major traffic arteries and geographic boundaries." Measure R authorized the city council to pass the redistricting ordinance that was targeted by this referendum.

Path to the ballot

When the city council voted six to three to accept the map, including the controversial District 7 boundaries, a group called the Berkeley Referendum Coalition began a petition drive to force a referendum on the redistricting ordinance. The coalition paid the petition drive management company Bay Area Petitions of Santa Cruz $5,000 to run the signature petition drive, and, on January 21, 2014, petitioners turned in 7,867 signatures to the Berkeley City Clerk. About 2,500 of these signatures were collected by volunteers, while the remainder was collected by paid circulators from the Bay Area Petitions of Santa Cruz. After a random sampling of the signatures, the Alameda County Registrar of Voters concluded that the petitions contained signatures numbering well over the 5,275 valid signatures required to force the city council to choose between rescinding the ordinance themselves and putting a referendum on the ballot. The city decided to put the redistricting map before voters in November.[2][5]

Councilmember Kriss Worthington (District 7), speaking to petition volunteers and supporters in response to the success of the referendum petition, said, “The odds were stacked against any sane person getting signatures. But all of you realized that the conventional wisdom does not always rule the day.”[12][4]

Councilman Worthington also said, "The fact that about 15 percent of the voters of Berkeley signed the referendum petition, during (December) the single month that is the hardest to get signatures in Berkeley is an amazing testament to how bad of a plan this was."[4]

Related measures

See also

- Incorporation, merging and boundaries of local jurisdictions on the ballot

- November 4, 2014 ballot measures in California

- Alameda County, California ballot measures

- Notable local measures on the ballot

External links

Footnotes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Berkeleyside, "Berkeley redistricting map splits council, community," December 18, 2013

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Berkeleyside, "Berkeley redistricting referendum effort prevails," February 3, 2014

- ↑ Berkeley City Clerk website, city council meeting agenda February 25, 2014

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Contra Costa Times, "Berkeley council delays redistricting decisions," February 26, 2014

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 The Daily Californian, "City redistricting to be decided in November election," March 12, 2014

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Berkeleyside, "Judge rules for council-majority-approved map in bitter Berkeley redistricting battle," April 30, 2014

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 7.7 7.8 Alameda County Elections Office, "Ballot Measure information document," archived August 15, 2014

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 Note: This text is quoted verbatim from the original source. Any inconsistencies are attributable to the original source.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Berkeleyside, "Op-ed: We don’t need a redistricting referendum," January 10, 2014

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 The Daily Californian, "Berkeley residents step up to foot the bill of recent referendum campaign," February 6, 2014

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 Berkeleyside, "Long-time Berkeley progressives back referendum drive," February 3, 2014

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 The Daily Californian, "Berkeley Referendum Coalition celebrates success, plans to meet Sunday," February 14, 2014

|

State of California Sacramento (capital) |

|---|---|

| Elections |

What's on my ballot? | Elections in 2025 | How to vote | How to run for office | Ballot measures |

| Government |

Who represents me? | U.S. President | U.S. Congress | Federal courts | State executives | State legislature | State and local courts | Counties | Cities | School districts | Public policy |