Help us improve in just 2 minutes—share your thoughts in our reader survey.

Congressional Review Act

| Administrative State |

|---|

| Five Pillars of the Administrative State |

| •Agency control • Executive control • Judicial control •Legislative control • Public Control |

| Click here for more coverage of the administrative state on Ballotpedia.

|

| Click here to access Ballotpedia's administrative state legislation tracker. |

What is the Congressional Review Act (CRA)?

The Congressional Review Act (CRA) is a law passed in 1996 that allows Congress to review and reject new federal regulations created by government agencies. It is a form of legislative oversight of agency actions. Under the CRA, Congress has 60 working days after a rule has been submitted to Congress to introduce a joint resolution of disapproval. If Congress approves the resolution and the president signs it, the targeted rule is nullified.

This process of overturning an agency rule is simpler than other lawmaking procedures. Joint resolutions of disapproval bypass the filibuster in the Senate by limiting debate to 10 hours, sometimes less. They are also not subject to proposals for amendments, motions to postpone, or motions to proceed to other business.[1]

Why does it matter?

The CRA is a method of legislative oversight of agency regulations; it and similar agency oversight mechanisms are part of Ballotpedia's legislative control pillar of the administrative state. It is related to debates about the separation of powers. As of June 2025, the CRA has been used to repeal 36 rules, 32 of which have been during Donald Trump's presidencies (16 rules repealed during each).

What are the key arguments?

The CRA is part of a larger argument about the balance of power between executive agencies and the legislature.

Supporters of the CRA argue that it fosters accountability and congressional oversight, helping to prevent agency overreach and alignment of agency regulation with the priorities of elected leaders. Critics argue that the CRA undermines the ability of agencies to develop effective and consistent regulations and a stable regulatory framework.

What's the background?

The CRA was passed in 1996 and signed into law by President Bill Clinton (D).[2] It is part of the Small Business Regulatory Enforcement Fairness Act section of the Contract with America Advancement Act of 1996, which was a legislative package designed to implement reforms that Republicans promised to enact during the 1994 election campaign in the Contract With America.[2][3][4]

Since the CRA was enacted in 1996, it has been used to repeal 36 rules as of June 2025. More than 500 joint resolutions of disapproval were introduced between 1996 and March 2025. Over 109,000 federal rules were promulgated in that time.[5][6]

Dive deeper:

Click the links below to jump to the section:

- Background

- How the CRA works

- Historical usage of the CRA

- Noteworthy events

Background

Passage of the CRA

The Congressional Review Act was passed in 1996 and signed into law by President Bill Clinton (D).[2] It is part of the Small Business Regulatory Enforcement Fairness Act section of the Contract with America Advancement Act of 1996, which was a legislative package designed to implement reforms that Republicans promised to enact during the 1994 election campaign in the Contract With America.[2][3][4] The Contract included promises to reform congressional structure, social security, taxes, budgeting, congressional term limits, and regulatory policy.[7] Republicans claimed that the reforms contained in the Contract would "be the end of government that is too big, too intrusive, and too easy with the public's money."[7]

Since the CRA was enacted in 1996, it has been used to repeal 36 rules as of June 2025. More than 500 joint resolutions of disapproval were introduced between 1996 and March 2025. Over 109,000 federal rules were promulgated in that time.[8][9] Of these 500 introduced joint resolutions, 32 were passed by Congress and signed by the President within the first year of a new administration, when the President and a majority in each chamber of Congress were from the same party. The CRA is most frequently used when a new president takes office, with most disapprovals targeting rules from the outgoing administration, often of the opposite party. Notable actions include:

- George W. Bush (R) signed the first resolution of disapproval in 2001.

- Donald Trump (R) signed 16 resolutions of disapproval in his first term — 15 in 2017 and one in 2018.

- Joe Biden (D) signed three joint resolutions of disapproval in 2021.

- Donald Trump (R) signed 16 joint resolutions of disapproval in his second term as of June 20, 2025.

Presidents have vetoed 17 CRA resolutions. Click here to learn more about how the CRA has been used since its enactment.

Purpose of the CRA

With the CRA, Congress intended to establish a review system to address the complaint that "Congress [had] effectively abdicated its constitutional role as the national legislature in allowing federal agencies so much latitude in implementing and interpreting congressional enactments," according to the official legislative history of the law.[3] The same historical record states, "Congressional review gives the public the opportunity to call the attention of politically accountable, elected officials to concerns about new agency rules. If these concerns are sufficiently serious, Congress can stop the rule."[3]

The CRA is a legislative oversight mechanism that requires a proactive effort by Congress to overturn federal agency rules. Unlike other mechanisms, such as the Regulations from the Executive in Need of Scrutiny (REINS) Act, which would impose automatic legislative approval for major rules before they take effect, the CRA operates reactively. Congress must introduce and pass a joint resolution of disapproval for a rule to be invalidated, and the President must sign it to finalize the repeal.

How the CRA works

Overview

Under the Congressional Review Act, a new final rule may be invalidated by a joint resolution of disapproval passed by Congress and signed by the president.[10] The resolution also prevents the agency from issuing a similar rule in the future unless authorized by new legislation, and it bars judicial review—meaning that a resolution of disapproval cannot be challenged in federal court.[10] The law requires agencies to submit new and interim final rules to both houses of Congress and the Government Accountability Office (GAO) in order to take effect.[10] The submission should include (1) a copy of the rule; (2) a general description; (3) the proposed effective date; and (4) cost-benefit and other analyses required by the Paperwork Reduction Act and the Administrative Procedure Act.[10][11]

The CRA, according to an overview published by the Congressional Research Service (CRS), "adopts the broadest definition of rule contained in the Administrative Procedure Act (APA)," which includes agency actions such as notices and guidance documents, in addition to final rules.[12]

Joint resolution of disapproval

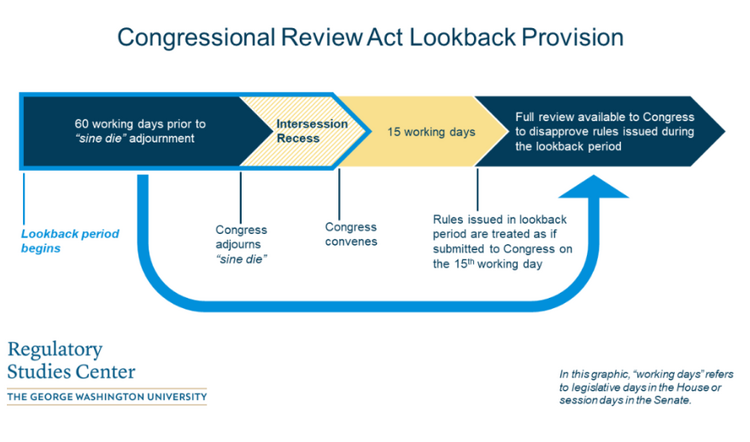

Members of Congress may introduce a CRA resolution of disapproval within 60 days of a new rule notification by an agency.[10] That time period is counted as 60 working days of a single session.[10] If a rule is issued and submitted to Congress with less than 60 working days left in the congressional session, the next session of Congress is given time to introduce a resolution of disapproval. In this case, rules are treated as if introduced on the 15th day of the new congressional session, giving Congress a lookback window to consider CRA resolutions of disapproval against regulations put in place near the end of the previous administration.[13] The CRA incorporates the definition of “rule” used in the Administrative Procedure Act which, in addition to regulations, includes guidance documents and policy memoranda.[10]

In the Senate, the CRA provides a process for Senate bills to circumvent two obstacles— committee passage and voting— if the chamber acts upon the resolution of disapproval within 60 days of the agency notifying Congress of the rule:[10][14]

- If a Senate committee has not reported a resolution of disapproval after 20 calendar days, 30 senators can sign a petition to discharge the resolution from the committee and place it on the Senate calendar.Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; invalid names, e.g. too many - Once on the Senate Calendar, it is not subject to amendments, motions to postpone, or motions to proceed to other business. The debate on a resolution is limited to 10 hours, though it can be further limited. Resolutions must be voted on immediately following their debate.Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; invalid names, e.g. too many

In the House, the resolution is often considered under a closed special rule reported by the Rules Committee, according to the Congressional Research Service.[4] All votes under a CRA resolution are simple majority votes.[4] As with other legislation, Congress may override a presidential veto of a CRA resolution by a two-thirds vote of members.[4]

If a resolution of disapproval passes, the targeted rule does not take effect.[10] If the rule is already in effect, the resolution blocks enforcement, and the agency must act as though the rule never took effect.[10]

The CRA does not apply to rules governing agency procedures, management, and personnel.[10] A CRA resolution cannot invalidate parts of a rule or more than one rule at a time.[10]

Review of major rules

- See also: Major rule

The CRA includes two additional provisions for rules that are designated as major—that is, rules expected to cost the private sector at least $100 million annually or that have significant impacts on employment, investment, competition or prices:[11]

- First, the comptroller general at GAO is required to submit an assessment of the rule to the congressional committees of jurisdiction within 15 calendar days of the rule's submission or its publication in the Federal Register.[11]

- Second, Congress may delay a major rule from taking effect in order to have more time to consider the rule beyond the standard 60 days under the CRA.[10]

The law gives the administrator of the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs (OIRA) the responsibility for determining whether a new rule is major.[10]

Historical usage of the CRA

Before 2017, the only successful use of the CRA was in 2001 when the recently sworn-in Congress and President George W. Bush (R) reversed an ergonomic standards rule issued by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration during the final months of the previous administration.

During his presidency, Barack Obama (D) vetoed five CRA resolutions addressing environmental, labor, and financial policy.[15][16]

In the first four months of his first term, President Donald Trump (R) signed 14 CRA resolutions from Congress undoing a variety of rules issued near the end of Barack Obama's (D) presidency.[17][18][15][19] In total, Congress repealed 16 rules using the CRA during Trump's first term.[20][21] Trump vetoed one resolution of disapproval near the end of his first term in 2020.[22]

On June 30, 2021, Joe Biden (D) signed three CRA resolutions of disapproval, bringing the total number of rules repealed through the CRA to 20.[23][24][25] Biden also vetoed 11 resolutions of disapproval during 2023 and 2024.

In his second term, Donald Trump (R) has signed 16 joint resolutions of disapproval as of June 20, 2025.

Noteworthy events

Beyond repealing rules made by agencies following the rulemaking process, the Trump administration took steps to apply the CRA to guidance documents, including guidance issued by independent federal agencies.

May 21, 2018: CFPB guidance repealed

On May 21, 2018, President Trump signed a CRA resolution invalidating a guidance document issued by the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB).[20] It was the first time that the CRA was used to overturn a guidance document rather than a rule issued through the rulemaking procedures of the Administrative Procedure Act. The repeal resolution was introduced to Congress in March 2018 by Sen. Jerry Moran (R-Kan.). The U.S. Senate passed the resolution on April 18, 2018. The vote was 51-47, with all present Republicans and West Virginia Democrat Joe Manchin voting in favor. Sens. John McCain (R-Ariz.) and Tammy Duckworth (D-Ill.) were absent.[30] The U.S. House of Representatives passed a corresponding resolution on May 8 by a vote of 234-175. The measure was mainly supported by Republicans, with 11 Democrats also voting for the resolution.[31]

Guidance documents, agency documents created to explain, interpret, or advise interested parties about rules, laws, and procedures, are not typically subject to the CRA. However, on December 5, 2017, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) issued a determination that the CFPB's indirect auto lending bulletin was a rule for the purposes of the CRA. The GAO made this determination in response to a study request from Sen. Pat Toomey (R-Pa.).[32]

April 11, 2019: Memo outlined White House review of independent agencies and guidance documents

An April 11 guidance memo published by the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) established rules for compliance with the CRA.[33] It amended earlier OMB guidance for implementing the CRA published in 1999 to affirm that Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs (OIRA) review procedures apply to historically independent agencies. It also stated that some guidance documents fall within the definition of rules subject to the CRA.[33]

The guidance memo told agencies not to publish any rules in the Federal Register or anywhere else until both OIRA determined whether the rule is major and the agency has complied with the CRA.[33]

The memo affirmed the broad scope of the CRA over rules coming out of the administrative state. Under Clinton-era Executive Order 12866, agencies have to submit any significant regulatory actions to OIRA for review.[33] However, agencies do not submit all CRA-covered actions to OIRA.[34] In addition to notice-and-comment rules, the new OMB memo said that agencies have to submit statements of policy and interpretive rules to OIRA and Congress.[33] That instruction included guidance documents, which agencies often fail to submit for CRA review.[34] The memo required agencies to include a CRA compliance statement in the body of new rules, which gives Congress notice that OIRA determined whether the rule was major.[33]

Guidance documents, memoranda, and other statements by agencies issued outside the requirements of the Administrative Procedure Act (APA) can have practical effects on the public even if they are not always legally binding. Some critics of the administrative state have called those kinds of agency actions regulatory dark matter. The OMB memo included regulatory dark matter within the CRA review process and could result in "more accurate accounting of the economic effects of rules and guidance, with the opportunity for more informed action by Congress and the public," according to professor Bridget C. E. Dooling.[33][34] Others saw the memo as more than a clarification of the existing requirements of the CRA. The memo was "a controversial step that has long been a goal of conservative groups," according to Damien Paletta, writing for the Washington Post.[35] Paletta also wrote that "[t]he step could have the effect of nullifying or blocking a range of new regulatory initiatives."[35]

April 4, 2025: Senate parliamentarian ruled against CRA resolutions that disapprove of EPA waivers

On April 4, 2025, the Senate Parliamentarian made a determination that Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) waivers are not subject to motions of disapproval under the CRA.[36] The EPA had previously granted waivers to the Clean Air Act (CAA), under which the EPA agreed to allow California to adopt more-stringent motor vehicle emissions standards than those promulgated under the CAA. As of April 4, 2025, Congress was considering three CRA resolutions of disapproval of the EPA waivers.[37] The Government Accountability Office had previously ruled that these waivers were not rules under the CRA, and that they were therefore not subject to the resolution of disapproval process under the CAA.[11] The parliamentarian's non-binding determination on April 4, 2025 agreed with this position, ruling that the EPA waivers were not rules under the CRA and were therefore not subject to the motion of disapproval process.[38]

See also

- Congressional Review Act Learning Journey

- Federal agency rules repealed under the Congressional Review Act

- Uses of the Congressional Review Act during the Trump administrations

- Uses of the Congressional Review Act during the Biden administration

- Congress votes to repeal an agency guidance document for the first time

- U.S. Government Accountability Office

- Office of Management and Budget

- Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs

- Related terms and laws:

External links

- Congressional Review Act (5 U.S. Code Chapter 8)

- U.S. Government Accountability Office

- Search Google News for this topic

Footnotes

- ↑ Columbian College of Arts & Sciences Regulatory Studies Center, "A Lookback at the Law: How Congress Uses the CRA," March 6, 2025

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Congress, "H.R.3136 - Contract with America Advancement Act of 1996," accessed April 23, 2019

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Congressional Record, "S3683, Congressional Review Title of H.R. 3136," April 18, 1996

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 Congressional Research Service, "In Focus: The Congressional Review Act (CRA)," accessed April 22, 2019

- ↑ Regulatory Studies Center, "Congressional Review Act," accessed January 14, 2025

- ↑ Ballotpedia staff has tracked joint resolutions of disapproval under the CRA introduced since the beginning of the 118th Congress.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 U.S. House of Representatives, "Republican Contract With America," accessed May 31, 2019

- ↑ Regulatory Studies Center, "Congressional Review Act," accessed January 14, 2025

- ↑ Ballotpedia staff has tracked joint resolutions of disapproval under the CRA introduced since the beginning of the 118th Congress.

- ↑ 10.00 10.01 10.02 10.03 10.04 10.05 10.06 10.07 10.08 10.09 10.10 10.11 10.12 10.13 Congressional Research Service, "The Congressional Review Act: Frequently Asked Questions," November 17, 2016

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 U.S. Government Accountability Office, "Congressional Review Act FAQs," accessed July 15, 2017 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "GAO" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ Congressional Research Service, "The Congressional Review Act (CRA): A Brief Overview," February 27, 2023

- ↑ Cornell Legal Information Institute, "5 U.S. Code § 801 - Congressional review," November 15, 2024

- ↑ George Washington University's Regulatory Studies Center, "A Lookback at the Law: How Congress Uses the CRA," November 15, 2024

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Smithsonian Magazine, "What Is the Congressional Review Act?" February 10, 2017

- ↑ Quartz, "The obscure law Donald Trump will use to unwind Obama's regulations," December 1, 2016

- ↑ U.S. News, "Democrats Push to Repeal Congressional Review Act," June 1, 2017

- ↑ The Hill, "The Congressional Review Act and a deregulatory agenda for Trump's second year," March 31, 2017

- ↑ New York Times, "Which Obama-Era Rules Are Being Reversed in the Trump Era," May 18, 2017

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Congress.gov, "S.J.Res.57," accessed May 22, 2018

- ↑ Congressional Record, "Vol. 167, No. 20: Proceedings and Debates of the 117th Congress, First Session," February 3, 2021

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedtrumpveto - ↑ Congress.gov, "S.J.Res.13 - A joint resolution providing for congressional disapproval under chapter 8 of title 5, United States Code, of the rule submitted by the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission relating to "Update of Commission's Conciliation Procedures"," accessed July 30, 2021

- ↑ Congress.gov, "S.J.Res.14 - A joint resolution providing for congressional disapproval under chapter 8 of title 5, United States Code, of the rule submitted by the Environmental Protection Agency relating to "Oil and Natural Gas Sector: Emission Standards for New, Reconstructed, and Modified Sources Review"," accessed July 30, 2021

- ↑ Congress.gov, "S.J.Res.15 - A joint resolution providing for congressional disapproval under chapter 8 of title 5, United States Code, of the rule submitted by the Office of the Comptroller of Currency relating to "National Banks and Federal Savings Associations as Lenders"," accessed July 30, 2021

- ↑ George Washington University Regulatory Studies Center, "Congressional Review Act Tracker 2017," accessed July 28, 2017

- ↑ Government Accountability Office, "Congressional Review Act FAQs," accessed July 31, 2017

- ↑ Reuters, "Trump kills class-action rule against banks, lightening Wall Street regulation," November 1, 2017

- ↑ Congress.gov, "S.J.Res.57," accessed May 22, 2018

- ↑ The Hill, "Senate repeals auto-loan guidance in precedent-shattering vote," April 18, 2018

- ↑ The New York Times, "House Votes to Dismantle Bias Rule in Auto Lending," May 8, 2018

- ↑ Government Accountability Office, "Applicability of the Congressional Review Act to Bulletin on Indirect Auto Lending and Compliance with the Equal Credit Opportunity Act," December 5, 2017

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 33.2 33.3 33.4 33.5 33.6 Office of Management and Budget, "Memorandum for the Heads of Executive Departments and Agencies," April 11, 2019

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 34.2 The Hill, "How independent are government agencies? OMB's move on 'major' rules may tell us," Bridget C.E. Dooling, April 13, 2019

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 Washington Post, "White House seeks tighter oversight of regulations issued by Fed and other independent agencies," Damian Paletta, April 11, 2019

- ↑ The Hill, "Senate parliamentarian says lawmakers can’t overturn California car rules — but Republicans may try anyway," Rachel Frazin, April 4, 2025

- ↑ E&E News by Politico, "House plows ahead with assault on California EPA waivers," Kelsey Brugger and Timothy Cama, April 4, 2025

- ↑ E&E News by Politico, "Senators weigh next move on California clean car rules," Kelsey Brugger, April 10, 2025