Redistricting in Michigan

Redistricting is the process by which new congressional and state legislative district boundaries are drawn. Each of Michigan's 13 United States Representatives and 148 state legislators are elected from political divisions called districts. United States Senators are not elected by districts, but by the states at large. District lines are redrawn every 10 years following completion of the United States census. The federal government stipulates that districts must have nearly equal populations and must not discriminate on the basis of race or ethnicity.[1][2][3][4]

Michigan was apportioned 13 seats in the U.S. House of Representatives after the 2020 census, one fewer than it received after the 2010 census. Click here for more information about redistricting in Michigan after the 2020 census.

Michigan’s congressional district boundaries became law on March 26, 2022, 60 days after the Michigan Independent Citizens Redistricting Commission (MICRC) published its report on the redistricting plans with the secretary of state.[5][6] On December 28, 2021, the Michigan Independent Citizens Redistricting Commission (MICRC) approved what was named the "Chestnut" map by a vote of 8-5. Two Democrats, two Republicans, and four nonpartisan members voted to approve the plan with the five remaining commissioners in favor of other plans. As required, "at least two commissioners who affiliate with each major party, and at least two commissioners who do not affiliate with either major party" voted in favor of the adopted map.[7]

On July 26, 2024, a three-judge panel of the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Michigan approved state Senate district boundaries submitted by the Michigan Independent Citizens Redistricting Commission (MICRC) on June 27, 2024, and authorized Michigan's secretary of state to implement the plan for the 2026 elections:[8]

| “ | On December 21, 2023, we unanimously held that the Michigan Independent Citizens Redistricting Commission violated the Equal Protection Clause of the U.S. Constitution when it drew the boundaries of thirteen state-legislative districts—seven House districts, and six Senate—predominantly on the basis of race. We therefore enjoined the Michigan Secretary of State, Jocelyn Benson, from holding further elections in those districts as they were drawn. ... The Commission has now submitted a revised Senate map, which Plaintiffs agree 'eliminates the predominate use of race that characterized' the previous plan. ... We have reviewed the record before us and agree that the new Senate map complies with this court’s December 21, 2023, opinion and order. ... Federal law provides us no basis to reject the Commission’s remedial Senate plan. The Secretary of State may proceed to implement the Commission’s remedial Senate plan for the next election cycle.[9] | ” |

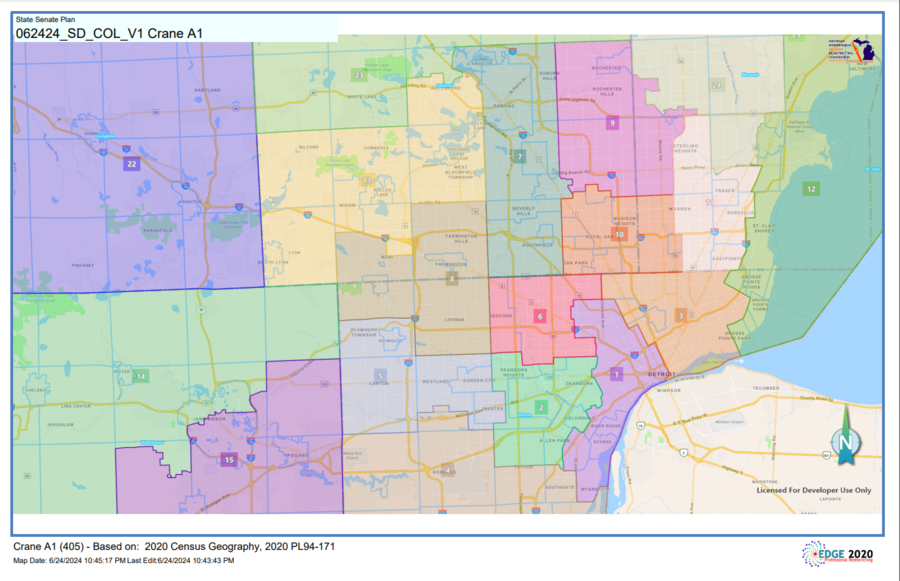

The MICRC voted on June 26 to approve the state Senate map called Crane A1.[10]

On March 27, 2024, the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Michigan approved new state House district boundaries drawn by the MICRC for use in the 2024 elections. According to the court order:[11]

| “ | On December 21, 2023, we unanimously held that the Michigan Independent Citizens Redistricting Commission violated the Equal Protection Clause of the U.S. Constitution when it drew the boundaries of thirteen state-legislative districts—seven House districts, and six Senate—predominantly on the basis of race. We therefore enjoined the Michigan Secretary of State, Jocelyn Benson, from holding further elections in those districts as they are currently drawn. ... The Commission has now submitted a revised House plan, to which the plaintiffs have submitted several objections. We have reviewed the record before us and now overrule those objections.[9] | ” |

The MICRC voted 10-3 on February 28, 2024, to adopt the new state House map known as “Motown Sound FC E1."

The U.S. District Court for the Western District of Michigan struck down the state House and Senate maps on December 21, 2023.[12]

Click here for more information on maps enacted after the 2020 census.

See the sections below for further information on the following topics:

- Background: A summary of federal requirements for redistricting at both the congressional and state legislative levels

- State process: An overview about the redistricting process in Michigan

- District maps: Information about the current district maps in Michigan

- Redistricting by cycle: A breakdown of the most significant events in Michigan's redistricting after recent censuses

- State legislation and ballot measures: State legislation and state and local ballot measures relevant to redistricting policy

- Political impacts of redistricting: An analysis of the political issues associated with redistricting

Background

This section includes background information on federal requirements for congressional redistricting, state legislative redistricting, state-based requirements, redistricting methods used in the 50 states, gerrymandering, and recent court decisions.

Federal requirements for congressional redistricting

According to Article I, Section 4 of the United States Constitution, the states and their legislatures have primary authority in determining the "times, places, and manner" of congressional elections. Congress may also pass laws regulating congressional elections.[13][14]

| “ | The Times, Places and Manner of holding Elections for Senators and Representatives, shall be prescribed in each State by the Legislature thereof; but the Congress may at any time by Law make or alter such Regulations, except as to the Places of chusing Senators.[9] | ” |

| —United States Constitution | ||

Article I, Section 2 of the United States Constitution stipulates that congressional representatives be apportioned to the states on the basis of population. There are 435 seats in the United States House of Representatives. Each state is allotted a portion of these seats based on the size of its population relative to the other states. Consequently, a state may gain seats in the House if its population grows or lose seats if its population decreases, relative to populations in other states. In 1964, the United States Supreme Court ruled in Wesberry v. Sanders that the populations of House districts must be equal "as nearly as practicable."[15][16][17]

The equal population requirement for congressional districts is strict. According to All About Redistricting, "Any district with more or fewer people than the average (also known as the 'ideal' population), must be specifically justified by a consistent state policy. And even consistent policies that cause a 1 percent spread from largest to smallest district will likely be unconstitutional."[17]

Federal requirements for state legislative redistricting

The United States Constitution is silent on the issue of state legislative redistricting. In the mid-1960s, the United States Supreme Court issued a series of rulings in an effort to clarify standards for state legislative redistricting. In Reynolds v. Sims, the court ruled that "the Equal Protection Clause [of the United States Constitution] demands no less than substantially equal state legislative representation for all citizens, of all places as well as of all races." According to All About Redistricting, "it has become accepted that a [redistricting] plan will be constitutionally suspect if the largest and smallest districts [within a state or jurisdiction] are more than 10 percent apart."[17]

State-based requirements

In addition to the federal criteria noted above, individual states may impose additional requirements on redistricting. Common state-level redistricting criteria are listed below.

- Contiguity refers to the principle that all areas within a district should be physically adjacent. A total of 49 states require that districts of at least one state legislative chamber be contiguous (Nevada has no such requirement, imposing no requirements on redistricting beyond those enforced at the federal level). A total of 23 states require that congressional districts meet contiguity requirements.[17][18]

- Compactness refers to the general principle that the constituents within a district should live as near to one another as practicable. A total of 37 states impose compactness requirements on state legislative districts; 18 states impose similar requirements for congressional districts.[17][18]

- A community of interest is defined by FairVote as a "group of people in a geographical area, such as a specific region or neighborhood, who have common political, social or economic interests." A total of 24 states require that the maintenance of communities of interest be considered in the drawing of state legislative districts. A total of 13 states impose similar requirements for congressional districts.[17][18]

- A total of 42 states require that state legislative district lines be drawn to account for political boundaries (e.g., the limits of counties, cities, and towns). A total of 19 states require that similar considerations be made in the drawing of congressional districts.[17][18]

Methods

In general, a state's redistricting authority can be classified as one of the following:[19]

- Legislature-dominant: In a legislature-dominant state, the legislature retains the ultimate authority to draft and enact district maps. Maps enacted by the legislature may or may not be subject to gubernatorial veto. Advisory commissions may also be involved in the redistricting process, although the legislature is not bound to adopt an advisory commission's recommendations.

- Commission: In a commission state, an extra-legislative commission retains the ultimate authority to draft and enact district maps. A non-politician commission is one whose members cannot hold elective office. A politician commission is one whose members can hold elective office.

- Hybrid: In a hybrid state, the legislature shares redistricting authority with a commission.

Gerrymandering

- See also: Gerrymandering

The term gerrymandering refers to the practice of drawing electoral district lines to favor one political party, individual, or constituency over another. When used in a rhetorical manner by opponents of a particular district map, the term has a negative connotation but does not necessarily address the legality of a challenged map. The term can also be used in legal documents; in this context, the term describes redistricting practices that violate federal or state laws.[1][20]

For additional background information about gerrymandering, click "[Show more]" below.

The phrase racial gerrymandering refers to the practice of drawing electoral district lines to dilute the voting power of racial minority groups. Federal law prohibits racial gerrymandering and establishes that, to combat this practice and to ensure compliance with the Voting Rights Act, states and jurisdictions can create majority-minority electoral districts. A majority-minority district is one in which a racial group or groups comprise a majority of the district's populations. Racial gerrymandering and majority-minority districts are discussed in greater detail in this article.[21]

The phrase partisan gerrymandering refers to the practice of drawing electoral district maps with the intention of favoring one political party over another. In contrast with racial gerrymandering, on which the Supreme Court of the United States has issued rulings in the past affirming that such practices violate federal law, the high court had not, as of November 2017, issued a ruling establishing clear precedent on the question of partisan gerrymandering. Although the court has granted in past cases that partisan gerrymandering can violate the United States Constitution, it has never adopted a standard for identifying or measuring partisan gerrymanders. Partisan gerrymandering is described in greater detail in this article.[22][23]Recent court decisions

The Supreme Court of the United States has, in recent years, issued several decisions dealing with redistricting policy, including rulings relating to the consideration of race in drawing district maps, the use of total population tallies in apportionment, and the constitutionality of independent redistricting commissions. The rulings in these cases, which originated in a variety of states, impact redistricting processes across the nation.

For additional background information about these cases, click "[Show more]" below.

Alexander v. South Carolina State Conference of the NAACP (2024)

Alexander v. South Carolina State Conference of the NAACP — This case concerns a challenge to the congressional redistricting plan that the South Carolina legislature enacted after the 2020 census. In January 2023, a federal three-judge panel ruled that the state's 1st Congressional District was unconstitutional and enjoined the state from conducting future elections using its district boundaries. The panel's opinion said, "The Court finds that race was the predominant factor motivating the General Assembly’s adoption of Congressional District No. 1...Defendants have made no showing that they had a compelling state interest in the use of race in the design of Congressional District No. 1 and thus cannot survive a strict scrutiny review."[24] Thomas Alexander (R)—in his capacity as South Carolina State Senate president—appealed the federal court's ruling, arguing: :In striking down an isolated portion of South Carolina Congressional District 1 as a racial gerrymander, the panel never even mentioned the presumption of the General Assembly’s “good faith.”...The result is a thinly reasoned order that presumes bad faith, erroneously equates the purported racial effect of a single line in Charleston County with racial predominance across District 1, and is riddled with “legal mistake[s]” that improperly relieved Plaintiffs of their “demanding” burden to prove that race was the “predominant consideration” in District 1.[25] The U.S. Supreme Court scheduled oral argument on this case for October 11, 2023.[26]

Moore v. Harper (2023)

- See also: Moore v. Harper

At issue in Moore v. Harper, was whether state legislatures alone are empowered by the Constitution to regulate federal elections without oversight from state courts, which is known as the independent state legislature doctrine. On November 4, 2021, the North Carolina General Assembly adopted a new congressional voting map based on 2020 Census data. The legislature, at that time, was controlled by the Republican Party. In the case Harper v. Hall (2022), a group of Democratic Party-affiliated voters and nonprofit organizations challenged the map in state court, alleging that the new map was a partisan gerrymander that violated the state constitution.[27] On February 14, 2022, the North Carolina Supreme Court ruled that the state could not use the map in the 2022 elections and remanded the case to the trial court for further proceedings. The trial court adopted a new congressional map drawn by three court-appointed experts. The United States Supreme Court affirmed the North Carolina Supreme Court's original decision in Moore v. Harper that the state's congressional district map violated state law. In a 6-3 decision, Chief Justice John Roberts wrote that the "Elections Clause does not vest exclusive and independent authority in state legislatures to set the rules regarding federal elections.[28]

Merrill v. Milligan (2023)

- See also: Merrill v. Milligan

At issue in Merrill v. Milligan, was the constitutionality of Alabama's 2021 redistricting plan and whether it violated Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act. A group of Alabama voters and organizations sued Secretary of State John Merrill (R) and the House and Senate redistricting chairmen, Rep. Chris Pringle (R) and Sen. Jim McClendon (R). Plaintiffs alleged the congressional map enacted on Nov. 4, 2021, by Gov. Kay Ivey (R) unfairly distributed Black voters. The plaintiffs asked the lower court to invalidate the enacted congressional map and order a new map with instructions to include a second majority-Black district. The court ruled 5-4, affirming the lower court opinion that the plaintiffs showed a reasonable likelihood of success concerning their claim that Alabama's redistricting map violated Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act.[29]

Gill v. Whitford (2018)

- See also: Gill v. Whitford

In Gill v. Whitford, decided on June 18, 2018, the Supreme Court of the United States ruled that the plaintiffs—12 Wisconsin Democrats who alleged that Wisconsin's state legislative district plan had been subject to an unconstitutional gerrymander in violation of the First and Fourteenth Amendments—had failed to demonstrate standing under Article III of the United States Constitution to bring a complaint. The court's opinion, penned by Chief Justice John Roberts, did not address the broader question of whether partisan gerrymandering claims are justiciable and remanded the case to the district court for further proceedings. Roberts was joined in the majority opinion by Associate Justices Anthony Kennedy, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Stephen Breyer, Samuel Alito, Sonia Sotomayor, and Elena Kagan. Kagan penned a concurring opinion joined by Ginsburg, Breyer, and Sotomayor. Associate Justice Clarence Thomas penned an opinion that concurred in part with the majority opinion and in the judgment, joined by Associate Justice Neil Gorsuch.[30]

Cooper v. Harris (2017)

- See also: Cooper v. Harris

In Cooper v. Harris, decided on May 22, 2017, the Supreme Court of the United States affirmed the judgment of the United States District Court for the Middle District of North Carolina, finding that two of North Carolina's congressional districts, the boundaries of which had been set following the 2010 United States Census, had been subject to an illegal racial gerrymander in violation of Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act. Justice Elena Kagan delivered the court's majority opinion, which was joined by Justices Clarence Thomas, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Stephen Breyer, and Sonia Sotomayor (Thomas also filed a separate concurring opinion). In the court's majority opinion, Kagan described the two-part analysis utilized by the high court when plaintiffs allege racial gerrymandering as follows: "First, the plaintiff must prove that 'race was the predominant factor motivating the legislature's decision to place a significant number of voters within or without a particular district.' ... Second, if racial considerations predominated over others, the design of the district must withstand strict scrutiny. The burden shifts to the State to prove that its race-based sorting of voters serves a 'compelling interest' and is 'narrowly tailored' to that end." In regard to the first part of the aforementioned analysis, Kagan went on to note that "a plaintiff succeeds at this stage even if the evidence reveals that a legislature elevated race to the predominant criterion in order to advance other goals, including political ones." Justice Samuel Alito delivered an opinion that concurred in part and dissented in part with the majority opinion. This opinion was joined by Chief Justice John Roberts and Justice Anthony Kennedy.[31][32][33]

Evenwel v. Abbott (2016)

- See also: Evenwel v. Abbott

Evenwel v. Abbott was a case decided by the Supreme Court of the United States in 2016. At issue was the constitutionality of state legislative districts in Texas. The plaintiffs, Sue Evenwel and Edward Pfenninger, argued that district populations ought to take into account only the number of registered or eligible voters residing within those districts as opposed to total population counts, which are generally used for redistricting purposes. Total population tallies include non-voting residents, such as immigrants residing in the country without legal permission, prisoners, and children. The plaintiffs alleged that this tabulation method dilutes the voting power of citizens residing in districts that are home to smaller concentrations of non-voting residents. The court ruled 8-0 on April 4, 2016, that a state or locality can use total population counts for redistricting purposes. The majority opinion was penned by Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg.[34][35][36][37]

Harris v. Arizona Independent Redistricting Commission (2016)

Harris v. Arizona Independent Redistricting Commission was a case decided by the Supreme Court of the United States in 2016. At issue was the constitutionality of state legislative districts that were created by the commission in 2012. The plaintiffs, a group of Republican voters, alleged that "the commission diluted or inflated the votes of almost two million Arizona citizens when the commission intentionally and systematically overpopulated 16 Republican districts while under-populating 11 Democrat districts." This, the plaintiffs argued, constituted a partisan gerrymander. The plaintiffs claimed that the commission placed a disproportionately large number of non-minority voters in districts dominated by Republicans; meanwhile, the commission allegedly placed many minority voters in smaller districts that tended to vote Democratic. As a result, the plaintiffs argued, more voters overall were placed in districts favoring Republicans than in those favoring Democrats, thereby diluting the votes of citizens in the Republican-dominated districts. The defendants countered that the population deviations resulted from legally defensible efforts to comply with the Voting Rights Act and obtain approval from the United States Department of Justice. At the time of redistricting, certain states were required to obtain preclearance from the U.S. Department of Justice before adopting redistricting plans or making other changes to their election laws—a requirement struck down by the United States Supreme Court in Shelby County v. Holder (2013). On April 20, 2016, the court ruled unanimously that the plaintiffs had failed to prove that a partisan gerrymander had taken place. Instead, the court found that the commission had acted in good faith to comply with the Voting Rights Act. The court's majority opinion was penned by Justice Stephen Breyer.[38][39][40]

Arizona State Legislature v. Arizona Independent Redistricting Commission (2015)

Arizona State Legislature v. Arizona Independent Redistricting Commission was a case decided by the Supreme Court of the United States in 2015. At issue was the constitutionality of the Arizona Independent Redistricting Commission, which was established by state constitutional amendment in 2000. According to Article I, Section 4 of the United States Constitution, "the Times, Places and Manner of holding Elections for Senators and Representatives shall be prescribed in each State by the Legislature thereof." The state legislature argued that the use of the word "legislature" in this context is literal; therefore, only a state legislature may draw congressional district lines. Meanwhile, the commission contended that the word "legislature" ought to be interpreted to mean "the legislative powers of the state," including voter initiatives and referenda. On June 29, 2015, the court ruled 5-4 in favor of the Arizona Independent Redistricting Commission, finding that "redistricting is a legislative function, to be performed in accordance with the state's prescriptions for lawmaking, which may include the referendum and the governor's veto." The majority opinion was penned by Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg and joined by Justices Anthony Kennedy, Stephen Breyer, Elena Kagan, and Sonia Sotomayor. Chief Justice John Roberts and Justices Clarence Thomas, Antonin Scalia, and Samuel Alito dissented.[41][42][43][44]Race and ethnicity

- See also: Majority-minority districts

Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 mandates that electoral district lines cannot be drawn in such a manner as to "improperly dilute minorities' voting power."

| “ | No voting qualification or prerequisite to voting, or standard, practice, or procedure shall be imposed or applied by any State or political subdivision to deny or abridge the right of any citizen of the United States to vote on account of race or color.[9] | ” |

| —Voting Rights Act of 1965[45] | ||

States and other political subdivisions may create majority-minority districts in order to comply with Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act. A majority-minority district is a district in which minority groups compose a majority of the district's total population. As of 2015, Michigan was home to two congressional majority-minority districts.[2][3][4]

Proponents of majority-minority districts maintain that these districts are a necessary hindrance to the practice of cracking, which occurs when a constituency is divided between several districts in order to prevent it from achieving a majority in any one district. In addition, supporters argue that the drawing of majority-minority districts has resulted in an increased number of minority representatives in state legislatures and Congress.[2][3][4]

Critics, meanwhile, contend that the establishment of majority-minority districts can result in packing, which occurs when a constituency or voting group is placed within a single district, thereby minimizing its influence in other districts. Because minority groups tend to vote Democratic, critics argue that majority-minority districts ultimately present an unfair advantage to Republicans by consolidating Democratic votes into a smaller number of districts.[2][3][4]

State process

- See also: State-by-state redistricting procedures

In Michigan, a non-politician commission is responsible for drawing both congressional and state legislative district plans. The commission comprises 13 members, including four Democrats, four Republicans, and five unaffiliated voters or members of minor parties. In order for a map to be enacted, at least seven members must vote for it, including at least two Democrats, two Republicans, and two members not affiliated with either major party.[46]

The Michigan Independent Citizens Redistricting Commission prepared this document specifically explaining the redistricting process after the 2020 census.

How incarcerated persons are counted for redistricting

States differ on how they count incarcerated persons for the purposes of redistricting. In Michigan, incarcerated persons are counted in the correctional facilities they are housed in.

District maps

Congressional districts

Michigan comprises 13 congressional districts. The table below lists Michigan's current U.S. Representatives.

| Office | Name | Party | Date assumed office | Date term ends |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| U.S. House Michigan District 1 | Jack Bergman | Republican | January 3, 2017 | January 3, 2027 |

| U.S. House Michigan District 2 | John Moolenaar | Republican | January 3, 2023 | January 3, 2027 |

| U.S. House Michigan District 3 | Hillary Scholten | Democratic | January 3, 2023 | January 3, 2027 |

| U.S. House Michigan District 4 | Bill Huizenga | Republican | January 3, 2023 | January 3, 2027 |

| U.S. House Michigan District 5 | Tim Walberg | Republican | January 3, 2023 | January 3, 2027 |

| U.S. House Michigan District 6 | Debbie Dingell | Democratic | January 3, 2023 | January 3, 2027 |

| U.S. House Michigan District 7 | Tom Barrett | Republican | January 3, 2025 | January 3, 2027 |

| U.S. House Michigan District 8 | Kristen McDonald Rivet | Democratic | January 3, 2025 | January 3, 2027 |

| U.S. House Michigan District 9 | Lisa McClain | Republican | January 3, 2023 | January 3, 2027 |

| U.S. House Michigan District 10 | John James | Republican | January 3, 2023 | January 3, 2027 |

| U.S. House Michigan District 11 | Haley Stevens | Democratic | January 3, 2019 | January 3, 2027 |

| U.S. House Michigan District 12 | Rashida Tlaib | Democratic | January 3, 2023 | January 3, 2027 |

| U.S. House Michigan District 13 | Shri Thanedar | Democratic | January 3, 2023 | January 3, 2027 |

State legislative maps

- See also: Michigan State Senate and Michigan House of Representatives

Michigan comprises 38 state Senate districts and 110 state House districts. State senators are elected every four years in partisan elections. State representatives are elected every two years in partisan elections. To access the state legislative district maps approved during the 2020 redistricting cycle, click here.

Redistricting by cycle

Redistricting after the 2020 census

Michigan was apportioned thirteen seats in the U.S. House of Representatives. This represented a net loss of one seat as compared to apportionment after the 2010 census.[47]

Enacted congressional district maps

Michigan’s congressional district boundaries became law on March 26, 2022, 60 days after the Michigan Independent Citizens Redistricting Commission (MICRC) published its report on the redistricting plans with the secretary of state.[48][6] On December 28, 2021, the Michigan Independent Citizens Redistricting Commission (MICRC) approved what was named the "Chestnut" map by a vote of 8-5. Two Democrats, two Republicans, and four nonpartisan members voted to approve the plan with the five remaining commissioners in favor of other plans. As required, "at least two commissioners who affiliate with each major party, and at least two commissioners who do not affiliate with either major party" voted in favor of the adopted map.[7]

The MICRC was established after voters approved a 2018 constitutional amendment that transferred the power to draw the state's congressional and legislative districts from the state legislature to an independent redistricting commission. Under the terms of the amendment, "Within 30 days after adopting a plan, the commission shall publish the plan and the material reports, reference materials, and data used in drawing it, including any programming information used to produce and test the plan." The adopted plan becomes law 60 days after the MICRC publishes that report.[7]

Beth LeBlanc of The Detroit News wrote that, “Unlike other congressional maps the commission had to choose from, Chestnut was set apart by its inclusion of Grand Rapids and Muskegon in the same district, its grouping of Battle Creek and Kalamazoo and its ability to keep Jackson County whole, instead of breaking off part of the county into an Ann Arbor area district.”[49] According to Clara Hendrickson and Todd Spangler of the Detroit Free Press, "According to three measures of partisan fairness based on statewide election data from the past decade, the map favors Republicans. But those measures also show a significant reduction in the Republican bias compared to the map drawn a decade ago by a Republican legislature, deemed one of the most politically biased maps in the country. One of the partisan fairness measures used by the commission indicates Democratic candidates would have an advantage under the new map."[50] This map took effect for Michigan’s 2022 congressional elections.

Congressional map

Below are the congressional maps in effect before and after the 2020 redistricting cycle.

Michigan Congressional Districts

until January 2, 2023

Click a district to compare boundaries.

Michigan Congressional Districts

starting January 3, 2023

Click a district to compare boundaries.

Reactions

Republican Commissioner Cynthia Orton said about the new maps, "We did the best job we could with the time and everything else we were given. What could be improved is what will be improved next time. We started with a lot of unknowns. It had never been done before in Michigan, and the next commission will have the benefit of us having done this before."[51] Democratic Commissioner Brittni Kellom said, "I know Black people all over, but particularly in Detroit, will continue, unfortunately, to do what they need to do to survive. Which is to galvanize and be active and to do what they need to do. ... Do I wish that there was more time to get it right? Absolutely."[51]

2020 presidential results

The table below details the results of the 2020 presidential election in each district at the time of the 2022 election and its political predecessor district.[52] This data was compiled by Daily Kos Elections.[53]

| 2020 presidential results by Congressional district, Michigan | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| District | 2022 district | Political predecessor district | ||

| Joe Biden |

Donald Trump |

Joe Biden |

Donald Trump | |

| Michigan's 1st | 39.3% | 59.1% | 40.6% | 57.9% |

| Michigan's 2nd | 35.0% | 63.2% | 37.1% | 61.2% |

| Michigan's 3rd | 53.3% | 44.8% | 47.4% | 50.6% |

| Michigan's 4th | 47.1% | 51.1% | 43.2% | 55.0% |

| Michigan's 5th | 37.1% | 61.2% | 41.4% | 56.9% |

| Michigan's 6th | 62.7% | 36.0% | 64.2% | 34.4% |

| Michigan's 7th | 49.4% | 48.9% | 48.8% | 49.6% |

| Michigan's 8th | 50.3% | 48.2% | 51.4% | 47.1% |

| Michigan's 9th | 34.6% | 64.0% | 34.4% | 64.2% |

| Michigan's 10th | 48.8% | 49.8% | 55.9% | 42.7% |

| Michigan's 11th | 59.3% | 39.4% | 51.6% | 47.1% |

| Michigan's 12th | 73.7% | 25.2% | 78.8% | 20.0% |

| Michigan's 13th | 74.2% | 24.6% | 79.5% | 19.5% |

Enacted state legislative district maps

State legislative maps enacted in 2024

On July 26, 2024, a three-judge panel of the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Michigan approved state Senate district boundaries submitted by the Michigan Independent Citizens Redistricting Commission (MICRC) on June 27, 2024, and authorized Michigan's secretary of state to implement the plan for the 2026 elections:[54]

| “ | On December 21, 2023, we unanimously held that the Michigan Independent Citizens Redistricting Commission violated the Equal Protection Clause of the U.S. Constitution when it drew the boundaries of thirteen state-legislative districts—seven House districts, and six Senate—predominantly on the basis of race. We therefore enjoined the Michigan Secretary of State, Jocelyn Benson, from holding further elections in those districts as they were drawn. ... The Commission has now submitted a revised Senate map, which Plaintiffs agree 'eliminates the predominate use of race that characterized' the previous plan. ... We have reviewed the record before us and agree that the new Senate map complies with this court’s December 21, 2023, opinion and order. ... Federal law provides us no basis to reject the Commission’s remedial Senate plan. The Secretary of State may proceed to implement the Commission’s remedial Senate plan for the next election cycle.[9] | ” |

The MICRC voted on June 26 to approve the state Senate map called Crane A1.[55]

On March 27, 2024, the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Michigan approved new state House district boundaries drawn by the MICRC for use in the 2024 elections. According to the court order:[56]

| “ | On December 21, 2023, we unanimously held that the Michigan Independent Citizens Redistricting Commission violated the Equal Protection Clause of the U.S. Constitution when it drew the boundaries of thirteen state-legislative districts—seven House districts, and six Senate—predominantly on the basis of race. We therefore enjoined the Michigan Secretary of State, Jocelyn Benson, from holding further elections in those districts as they are currently drawn. ... The Commission has now submitted a revised House plan, to which the plaintiffs have submitted several objections. We have reviewed the record before us and now overrule those objections.[9] | ” |

The MICRC voted 10-3 on February 28, 2024, to adopt the new state House map known as “Motown Sound FC E1."

The U.S. District Court for the Western District of Michigan struck down the state House and Senate maps on December 21, 2023.[12]

State Senate map

State House map

Reactions to 2024 state legislative maps (Senate)

After the court approved the Crane A1 map, independent MICRC commissioner Anthony Eid said:[57]

| “ | There’s certainly been a lot of ups and downs throughout this process. ... There have been things that as a commission we’ve gotten right and things we’ve gotten wrong. We’re currently in the middle of putting together a report that will go over a few of those things in great detail. But I think right now we’re just happy and relieved that we made it this far.[9] | ” |

Following the MICRC's selection of the new map, Republican commissioner Cynthia Orton said:[58]

| “ | I felt strongly that Crane A1 did answer the requirements that we needed to follow and what the court had ordered. ... I’m glad everyone was able to vote their conscience, vote what they felt was best.[9] | ” |

Democratic MICRC vice chair Brittni Kellom said:[59]

| “ | I don’t think that Crane A1 is the best representation for what Detroit citizens and beyond have expressed.[9] | ” |

Reactions to 2024 state legislative maps (House)

The Executive Director of the Michigan Independent Citizens Redistricting Commission, Edward Woods III, said the following in a news conference:[60]

| “ | Democracy won ... Despite doubts and concerns raised, the commission demonstrated once again that it could focus on its purpose to draw fair maps with citizen input. ... We appreciate the public input that overwhelmingly favored the Motown Sound FC E1 in making our job easier. We now have a clear road map to follow in completing the remedial State Senate plan.[9] | ” |

Independent Commissioner Rebecca Szetela, who did not vote for the map, said:[60]

| “ | I wish we could have agreed to make those changes to (districts) 16, 17, and 18 because I would have considered voting for it if those changes had been made.[9] | ” |

Former state House member Sherry Gay-Dagnogo was one of the plaintiffs in the Donald Agee, Jr. v. Secretary of State Jocelyn Benson case that led to the new House map. In a statement to the Michigan Advance, she reacted to the new map:[60]

| “ | While our expert Sean Trende demonstrated that the Motown Sound Map does not provide the greatest number of Black majority seats with the highest Black voting age population, we embrace the words of the late Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., that ‘the Arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice,’ and as such we are grateful that the Agee v. Benson lawsuit yielded a greater opportunity for Detroit voters to elect a candidate of their choice in seven house districts. Our focus now turns towards educating the community on the House Map changes, and drawing a new Senate map.[9] | ” |

State legislative maps enacted in 2022

On December 21, 2023, the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Michigan found Michigan's legislative maps to be unconstitutional and ordered the state to draw new maps before the 2024 elections. 13 Senate and House districts were identified as being racially gerrymandered in violation of the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. In its order, the three-judge panel wrote:[12]

| “ | The record here shows overwhelmingly—indeed, inescapably—that the Commission drew the boundaries of plaintiffs’ districts predominantly on the basis of race. We hold that those districts were drawn in violation of the Equal Protection Clause of the U.S. Constitution. ... We enjoin the Secretary of State from holding further elections in these districts as they are currently drawn. And we will direct that the parties appear before this court in early January to discuss how to proceed with redrawing them.[9] | ” |

The Michigan Independent Citizens Redistricting Commission (MICRC) approved new district boundaries for both the state Senate and state House of Representatives on December 28, 2021. The commission approved what was known as the "Linden" map for state Senate districts by a vote of 9-4 with two Democrats, two Republicans, and all five nonpartisan members supporting the proposal. The commission adopted what was known as the "Hickory" map for state House of Representatives districts by a vote of 11-2 with four Democrats, two Republicans, and all five nonpartisan members supporting it.[51][61] As required, the adopted map was approved by "at least two commissioners who affiliate with each major party, and at least two commissioners who do not affiliate with either major party."[7] The maps became law on March 26, 2022—60 days after the MICRC published a report on the redistricting plans with the secretary of state.[6]

Reactions to 2022 state legislative maps

According to The Detroit News, "The Linden Senate map...is expected to create districts that could yield 20 Democratic seats and 18 Republican seats. Senate Republicans currently have a 22-16 majority."[51] Clara Hendrickson of the Detroit Free Press wrote, "The map appears to create 19 solidly Democratic districts, 16 solidly Republican districts, one Republican-leaning district and two toss-up districts, according to election results from the past decade."[62]

Beth LeBlanc of The Detroit News wrote, "The Hickory House map...is expected to create districts that could produce 57 Democratic seats and 53 Republican seats. After the 2020 election, Michigan House Republicans had a 58-52 majority in the House."[51] Hendrickson wrote that, "The new map appears to create 41 solidly Democratic districts, 46 solidly Republican districts, nine Democratic-leaning districts, two Republican-leaning districts and 12 toss-up districts."[62] She also wrote, "Unlike the current map, there is no majority-Black district in the state Senate map adopted by the commission, while the state House map reduces the number of majority-Black districts in place today. Current and former state lawmakers from Detroit and civil rights leaders are vehemently opposed to how the new district lines reduce the share of Black voters. They argue that the elimination of majority-Black districts disenfranchises Black voters."[62] These maps took effect for Michigan’s 2022 legislative elections.

Drafting process

In Michigan, a non-politician commission is responsible for drawing both congressional and state legislative district plans. The commission comprises 13 members, including four Democrats, four Republicans, and five unaffiliated voters or members of minor parties. In order for a map to be enacted, at least seven members must vote for it, including at least two Democrats, two Republicans, and two members not affiliated with either major party.[63]

The Michigan Independent Citizens Redistricting Commission prepared this document specifically explaining the redistricting process after the 2020 census.

Timeline of 2021 map adoption

The Michigan Independent Citizens Redistricting Commission adopted the following timeline, as amended on December 28, 2021:[64]

- August 20, 2021 – September 30, 2021: Commission drafts initial maps prior to public hearings. Individual commissioners may also put forth draft maps for consideration.

- September 30, 2021 – November 5, 2021: Commission approves maps for display and feedback during public hearings.

- November 5, 2021 – December 30, 2021: Approved maps are published to begin a 45-day public comment period.

- December 30, 2021: Maps approved by a final vote with support from at least two commissioners of each affiliation. Maps become law 60 days after publication.

A detailed timeline is included below:

The MICRC also released a complete outline of the 2021-2022 redistricting process and procedures in Michigan.

Redistricting committees and/or commissions in 2021

The Michigan Independent Citizens Redistricting Commission was responsible for redistricting. The MICRC's website described the commission's mission as follows: "To lead Michigan's redistricting process to assure Michigan's Congressional, State Senate, and State House district lines are drawn fairly in a citizen-led, transparent process, meeting Constitutional mandates."[65] The commission's membership as of December 2020 was as follows:[66]

Pre-drafting developments

On August 6, 2021, the Michigan Independent Citizens Redistricting Commission announced it was considering hiring Mark Braden and law firm BakerHostetler as legal counsel. Braden was formerly chief counsel to the Republican National Committee and defended North Carolina Republican legislators in litigation surrounding the redrawing of North Carolina legislative districts in 2017. Critics said hiring the firm would compromise the independence of the committee. Secretary of State Jocelyn Benson (D) tweeted “Friendly reminder that Michigan’s Independent Redistricting Commission is just that – independent,” and anti-gerrymandering author David Daley said the firm was "infamous for advising and defending some of the most egregious GOP gerrymanders of the last decade." Committee spokesperson Edward Woods III said BakerHostetler was the only firm to submit a proposal: “We sent out two requests for litigation counsel. Unfortunately, no one responded the first time, and they are the only firm that responded this time. As always, we welcome and consider public input in making our decisions openly and transparently,” Woods said.[67][68]

MICRC approves congressional, legislative maps for public comment

The Michigan Independent Citizens Redistricting Commission (MICRC) approved a series of congressional and legislative maps on November 5, 2021, for a 45-day period of public comments. The Commission scheduled votes to approve final maps on December 30, 2021.[69][70]

Below are links to an interactive version for each proposed map:

Proposed congressional district maps

"Chestnut" plan

"Birch V2" plan

"Apple V2" plan

"Lange Congressional Map"

"Szetela Congressional Map"

Proposed state Senate district maps

"Cherry V2" plan

"Palm" plan

"Linden" plan

"Kellom Senate Map"

"Lange Senate Map"

"Szetela Senate Map"

Proposed state House district maps

"Pine V5" plan

"Magnolia" plan

"Hickory" plan

"Szetela House Map"

MICRC proposes maps for public hearings

The Michigan Independent Citizens Redistricting Commission (MICRC) voted on October 11, 2021, to approve four congressional maps, three state Senate maps, and three state House of Representatives maps for a final series of public hearings. The Commission released a spreadsheet summarizing the maps here:[71][72]

Spreadsheet of MICRC proposed maps

Map images can be viewed via the state's redistricting interface using the links below:

Congressional district maps

Redistricting Plan #201

Redistricting Plan #218

Redistricting Plan #219

Redistricting Plan #230

State Senate district maps

Redistricting Plan #199

Redistricting Plan #220

Redistricting Plan #226

State House of Representative district maps

Redistricting Plan #227

Redistricting Plan #228

Redistricting Plan #229

Apportionment and release of census data

Apportionment is the process by which representation in a legislative body is distributed among its constituents. The number of seats in the United States House of Representatives is fixed at 435. The United States Constitution dictates that districts be redrawn every 10 years to ensure equal populations between districts. Every ten years, upon completion of the United States census, reapportionment occurs.[73]

Apportionment following the 2020 census

The U.S. Census Bureau delivered apportionment counts on April 26, 2021. Michigan was apportioned thirteen seats in the U.S. House of Representatives. This represented a net loss of one seat as compared to apportionment after the 2010 census.[74]

See the table below for additional details.

| 2020 and 2010 census information for Michigan | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State | 2010 census | 2020 census | 2010-2020 | ||||

| Population | U.S. House seats | Population | U.S. House seats | Raw change in population | Percentage change in population | Change in U.S. House seats | |

| Michigan | 9,911,626 | 14 | 10,084,442 | 13 | 172,816 | 1.74% | -1 |

Redistricting data from the Census Bureau

On February 12, 2021, the Census Bureau announced that it would deliver redistricting data to the states by September 30, 2021. On March 15, 2021, the Census Bureau released a statement indicating it would make redistricting data available to the states in a legacy format in mid-to-late August 2021. A legacy format presents the data in raw form, without data tables and other access tools. On May 25, 2021, Ohio Attorney General Dave Yost (R) announced that the state had reached a settlement agreement with the Census Bureau in its lawsuit over the Census Bureau's timetable for delivering redistricting data. Under the terms of the settlement, the Census Bureau agreed to deliver redistricting data, in a legacy format, by August 16, 2021.[75][76][77][78] The Census Bureau released the 2020 redistricting data in a legacy format on August 12, 2021, and in an easier-to-use format at data.census.gov on September 16, 2021.[79][80]

Court challenges

- If you are aware of any relevant lawsuits that are not listed here, please email us at editor@ballotpedia.org.

Donald Agee, Jr. et al. v. Jocelyn Benson

On December 21, 2023, the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Michigan found Michigan's legislative maps to be unconstitutional and ordered the state to draw new maps before the 2024 elections. 13 Senate and House districts were identified as being racially gerrymandered in violation of the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.[81] In its order, the three-judge panel wrote:

| “ | The record here shows overwhelmingly—indeed, inescapably—that the Commission drew the boundaries of plaintiffs’ districts predominantly on the basis of race. We hold that those districts were drawn in violation of the Equal Protection Clause of the U.S. Constitution. ... We enjoin the Secretary of State from holding further elections in these districts as they are currently drawn. And we will direct that the parties appear before this court in early January to discuss how to proceed with redrawing them.[12][9] | ” |

The court approved redrawn House and Senate maps in March and July 2024, respectively.[82][83]

On March 23, 2022, several African-American voters, including Donald Agee, Jr., sued Michigan Secretary of State Jocelyn Benson and Michigan's Independent Citizens Redistricting Commission, challenging the legislative maps that were drawn using data from the 2020 census. The lawsuit argued that Michigan's Independent Citizens Redistricting Commission used race as the predominant factor when drawing legislative districts in violation of the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. The lawsuit also argued that the commission intentionally reduced the number of majority African-American districts in the state legislature in violation of Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act. The plaintiffs requested that the court block the legislative maps created by Michigan's Independent Citizens Redistricting Commission and order the creation of new maps for the 2024 election cycle. Hearings were held in November of 2023.[81]

League of Women Voters of Michigan, et al v. Independent Citizens Redistricting Commission

On February 1, 2022, the League of Women Voters of Michigan, seven other organizations, and 13 Michigan voters filed a lawsuit against the Michigan Independent Citizens Redistricting Commission challenging the State House district boundaries that the commission approved on December 28, 2021. The plaintiffs argued that MICRC adopted a "State House map which provides a disproportionate advantage to the Republican Party" in violation of state laws and the state constitution.[84] On March 25, 2022, the Michigan Supreme Court denied the petition, saying "the Court is not persuaded that it should grant the requested relief."[85]

Robert Davis v. Independent Citizens Redistricting Commission

On September 16, 2021, the Michigan Supreme Court dismissed a lawsuit by Robert Davis to force the state's Independent Citizens Redistricting Commission to comply with a Sept. 17 deadline for approving new congressional and legislative district boundaries. Davis had sued the Commission on Sept. 7 asking the court to require the Commission’s compliance with Michigan’s constitutional deadlines to adopt new redistricting plans by November 1, 2021, and to publish plans 45 days before that for a period of public comment.[86][87]

In July 2021, the Michigan Supreme Court rejected a request by the Commission to extend the constitution's redistricting deadlines, saying that it was "not persuaded that it should grant the requested relief." At that time, the Commission said it would not meet the deadlines due to delays in receiving population data from the U.S. Census Bureau.

This is the first redistricting cycle conducted using Michigan Proposal 2, a state constitutional amendment that voters approved in 2018 which transferred the power to draw the state's congressional and legislative districts from the state legislature to an independent redistricting commission.

In re: Independent Citizens Redistricting Commission's duty to redraw districts by November 1, 2021

On April 20, 2021, the Michigan Independent Citizens Redistricting Commission petitioned the Supreme Court of Michigan to extend the constitution's redistricting deadline. Under the Michigan Constitution, the commission would be required to adopt new redistricting plans by November 1, 2021. It would be required to publish plans for public comment by September 17, 2021. However, in light of the delayed delivery of detailed redistricting data by the U.S. Census Bureau, the commission argued that it would "not be able to comply with the constitutionally imposed timeline." Instead, the commission asked that the state supreme court issue an order directing the commission to propose plans within 72 days of the receipt of redistricting data and to approve plans within 45 days thereafter.[88]

The state supreme court asked the Office of the Attorney General to assemble two separate teams to make arguments, one team in support of the commission's request and another opposed. The court heard oral arguments on June 21, 2021. Deputy Solicitor General Ann Sherman, speaking in support of the proposed deadline extensions, said "The very maps themselves could be challenged if they are drawn after the November 1 deadline." Assistant Attorney General Kyla Barranco, speaking in opposition, said, "There isn't harm in telling the commission at this point, 'Try your best with the data that you might be able to use and come September 17, maybe we'll have a different case.'"[89]

On July 9, 2021, the state supreme court rejected the commission's request to extend the deadlines. In its unsigned order, the court said that it was "not persuaded that it should grant the requested relief." Justice Elizabeth Welch wrote a concurrence, in which she said, "The Court’s decision is not a reflection on the merits of the questions briefed or how this Court might resolve a future case raising similar issues. It is indicative only that a majority of this Court believes that the anticipatory relief sought is unwarranted."[90]

Daunt v. Benson

On May 27, 2021, a three-judge panel of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit affirmed a lower court's judgment that the membership criteria for Michigan's Independent Citizens Redistricting Commission did not violate the First and Fourteenth Amendments.[91][92]

On November 6, 2018, voters approved Proposal 18-2, a constitutional amendment establishing a "commission of citizens with exclusive authority to adopt district boundaries for the Michigan Senate, Michigan House of Representatives, and U.S. Congress." That amendment set forth the following eligibility criteria for members of the commission, "who must not be currently, or have been in the past six years:"[91][92]

- A declared candidate for partisan federal, state, or local office.

- An elected partisan federal, state, or local official.

- An officer of member of the governing board of national, state, or local political party.

- An employee of the state legislature.

- "A paid consultant or employee of a federal, state, or local elected official or political candidates, of a federal state or local political candidate's campaign, or of a political action committee."

- "Any person who is registered as a lobbyist agent with the Michigan bureau of elections, or any employee of such person."

- "An unclassified state employee who is exempt from classification in state civil service ... except for employees of courts of record, employees of the state institutions of higher education, and persons in the armed forces of the state."

On July 30, 2019, a group of Michigan voters filed suit in the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Michigan, alleging that "their exclusion from the Commission based on these partisan ties violates the First and Fourteenth Amendments." The district court ultimately dismissed the plaintiffs' complaint, a decision which prompted the appeal to the Sixth Circuit.[91][92]

The three-judge panel – Judges Karen Moore, Ronald Gilman, and Chad Readler – unanimously affirmed the district court's decision. Writing for the court, Judge Moore said, "Michigan's interest in cleansing its redistricting process of political conflicts of interest and the appearance thereof is ample justification for the limited burdens that the Amendment's eligibility criteria impose on those who would like to be considered for the Commission. Although claims of unconstitutional partisan gerrymandering may be nonjusticiable, Michigan is free to employ its political process to address the issue head on. It did so, adopting the Amendment after Michiganders overwhelmingly voted in favor of Proposal 18-2, and its eligibility criteria for the Commission do not offend the First or Fourteenth Amendments.[91][92]

Aftermath of redistricting

In 2018, Michigan voters approved a ballot measure creating an independent redistricting commission to draw the state's congressional and legislative maps. The commission was first used in the 2020 redistricting cycle.[93] Before this, the state legislature drew Michigan's maps. Four Republicans, four Democrats, and five independents made up the new commission, which took public comments on the maps into consideration.[94] The commission drew new legislative maps and approved them on December 28, 2021.[95]

In describing the old maps, Michigan Advance said: "In the past, the Legislature was in charge of drawing new districts every decade, with the governor’s sign off, which typically resulted in maps that protected incumbents and the party in charge."[96] A 2016 analysis by the Associated Press found: "Traditional battlegrounds such as Michigan, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, Florida and Virginia were among those with significant Republican advantages in their U.S. or state House races."[97]

Political officials from both parties expected the new maps to create more competitive elections. In an interview with the Huffington Post, Jessica Post, the president of the Democratic Legislative Campaign Committee, said: "We see Michigan as a huge opportunity because of the newly drawn fair maps.”[98] State Senate President Mike Shirkey (R) said he had: "100 percent confidence we’re going to retain the majority... But I have an equal level of confidence that we’re having to work harder this time than we have in probably 35 years.”[99] The two parties combined to spend $30 million in ads, which was among the highest for state legislative races in the country.[100]

Heading into the elections, the state legislature was controlled by Republicans, with Democrats last controlling the state House in 2010 and the state Senate in 1984.[101]

In the 2022 elections, Democrats won a 56-54 majority in the state House and a 20-18 majority in the state Senate.[102] This resulted in a Democratic trifecta, giving them control of state government. In discussing the results, Professor Matt Grossman said: "Under the new maps, the parties have to compete over districts with minimal partisan lanes as well as those that have more normally Republican voters and those that have more normally Democratic voters. This produced a real change. If you add up all the votes statewide for the House and the Senate Democrats got more votes by one and 1.5% in the two chambers, and they will end up with similarly small advantages in seats."[103] Douglas Clark, a Republican who served on the redistricting commission, said: “Depending on the issues of the election and depending on the candidates, some of these districts can go either way -- they can go Republican or they can go Democrat... In this instance in this election, more of them went Democrat."[104]

Background

This section includes background information on federal requirements for congressional redistricting, state legislative redistricting, state-based requirements, redistricting methods used in the 50 states, gerrymandering, and recent court decisions.

Federal requirements for congressional redistricting

According to Article I, Section 4 of the United States Constitution, the states and their legislatures have primary authority in determining the "times, places, and manner" of congressional elections. Congress may also pass laws regulating congressional elections.[105][106]

| “ | The Times, Places and Manner of holding Elections for Senators and Representatives, shall be prescribed in each State by the Legislature thereof; but the Congress may at any time by Law make or alter such Regulations, except as to the Places of chusing Senators.[9] | ” |

| —United States Constitution | ||

Article I, Section 2 of the United States Constitution stipulates that congressional representatives be apportioned to the states on the basis of population. There are 435 seats in the United States House of Representatives. Each state is allotted a portion of these seats based on the size of its population relative to the other states. Consequently, a state may gain seats in the House if its population grows or lose seats if its population decreases, relative to populations in other states. In 1964, the United States Supreme Court ruled in Wesberry v. Sanders that the populations of House districts must be equal "as nearly as practicable."[15][107][17]

The equal population requirement for congressional districts is strict. According to All About Redistricting, "Any district with more or fewer people than the average (also known as the 'ideal' population), must be specifically justified by a consistent state policy. And even consistent policies that cause a 1 percent spread from largest to smallest district will likely be unconstitutional."[17]

Federal requirements for state legislative redistricting

The United States Constitution is silent on the issue of state legislative redistricting. In the mid-1960s, the United States Supreme Court issued a series of rulings in an effort to clarify standards for state legislative redistricting. In Reynolds v. Sims, the court ruled that "the Equal Protection Clause [of the United States Constitution] demands no less than substantially equal state legislative representation for all citizens, of all places as well as of all races." According to All About Redistricting, "it has become accepted that a [redistricting] plan will be constitutionally suspect if the largest and smallest districts [within a state or jurisdiction] are more than 10 percent apart."[17]

State-based requirements

In addition to the federal criteria noted above, individual states may impose additional requirements on redistricting. Common state-level redistricting criteria are listed below.

- Contiguity refers to the principle that all areas within a district should be physically adjacent. A total of 49 states require that districts of at least one state legislative chamber be contiguous (Nevada has no such requirement, imposing no requirements on redistricting beyond those enforced at the federal level). A total of 23 states require that congressional districts meet contiguity requirements.[17][18]

- Compactness refers to the general principle that the constituents within a district should live as near to one another as practicable. A total of 37 states impose compactness requirements on state legislative districts; 18 states impose similar requirements for congressional districts.[17][18]

- A community of interest is defined by FairVote as a "group of people in a geographical area, such as a specific region or neighborhood, who have common political, social or economic interests." A total of 24 states require that the maintenance of communities of interest be considered in the drawing of state legislative districts. A total of 13 states impose similar requirements for congressional districts.[17][18]

- A total of 42 states require that state legislative district lines be drawn to account for political boundaries (e.g., the limits of counties, cities, and towns). A total of 19 states require that similar considerations be made in the drawing of congressional districts.[17][18]

Methods

In general, a state's redistricting authority can be classified as one of the following:[108]

- Legislature-dominant: In a legislature-dominant state, the legislature retains the ultimate authority to draft and enact district maps. Maps enacted by the legislature may or may not be subject to gubernatorial veto. Advisory commissions may also be involved in the redistricting process, although the legislature is not bound to adopt an advisory commission's recommendations.

- Commission: In a commission state, an extra-legislative commission retains the ultimate authority to draft and enact district maps. A non-politician commission is one whose members cannot hold elective office. A politician commission is one whose members can hold elective office.

- Hybrid: In a hybrid state, the legislature shares redistricting authority with a commission.

Gerrymandering

- See also: Gerrymandering

The term gerrymandering refers to the practice of drawing electoral district lines to favor one political party, individual, or constituency over another. When used in a rhetorical manner by opponents of a particular district map, the term has a negative connotation but does not necessarily address the legality of a challenged map. The term can also be used in legal documents; in this context, the term describes redistricting practices that violate federal or state laws.[1][20]

For additional background information about gerrymandering, click "[Show more]" below.

The phrase racial gerrymandering refers to the practice of drawing electoral district lines to dilute the voting power of racial minority groups. Federal law prohibits racial gerrymandering and establishes that, to combat this practice and to ensure compliance with the Voting Rights Act, states and jurisdictions can create majority-minority electoral districts. A majority-minority district is one in which a racial group or groups comprise a majority of the district's populations. Racial gerrymandering and majority-minority districts are discussed in greater detail in this article.[21]

The phrase partisan gerrymandering refers to the practice of drawing electoral district maps with the intention of favoring one political party over another. In contrast with racial gerrymandering, on which the Supreme Court of the United States has issued rulings in the past affirming that such practices violate federal law, the high court had not, as of November 2017, issued a ruling establishing clear precedent on the question of partisan gerrymandering. Although the court has granted in past cases that partisan gerrymandering can violate the United States Constitution, it has never adopted a standard for identifying or measuring partisan gerrymanders. Partisan gerrymandering is described in greater detail in this article.[109][110]Recent court decisions

The Supreme Court of the United States has, in recent years, issued several decisions dealing with redistricting policy, including rulings relating to the consideration of race in drawing district maps, the use of total population tallies in apportionment, and the constitutionality of independent redistricting commissions. The rulings in these cases, which originated in a variety of states, impact redistricting processes across the nation.

For additional background information about these cases, click "[Show more]" below.

Alexander v. South Carolina State Conference of the NAACP (2024)

Alexander v. South Carolina State Conference of the NAACP — This case concerns a challenge to the congressional redistricting plan that the South Carolina legislature enacted after the 2020 census. In January 2023, a federal three-judge panel ruled that the state's 1st Congressional District was unconstitutional and enjoined the state from conducting future elections using its district boundaries. The panel's opinion said, "The Court finds that race was the predominant factor motivating the General Assembly’s adoption of Congressional District No. 1...Defendants have made no showing that they had a compelling state interest in the use of race in the design of Congressional District No. 1 and thus cannot survive a strict scrutiny review."[24] Thomas Alexander (R)—in his capacity as South Carolina State Senate president—appealed the federal court's ruling, arguing: :In striking down an isolated portion of South Carolina Congressional District 1 as a racial gerrymander, the panel never even mentioned the presumption of the General Assembly’s “good faith.”...The result is a thinly reasoned order that presumes bad faith, erroneously equates the purported racial effect of a single line in Charleston County with racial predominance across District 1, and is riddled with “legal mistake[s]” that improperly relieved Plaintiffs of their “demanding” burden to prove that race was the “predominant consideration” in District 1.[111] The U.S. Supreme Court scheduled oral argument on this case for October 11, 2023.[112]

Moore v. Harper (2023)

- See also: Moore v. Harper

At issue in Moore v. Harper, was whether state legislatures alone are empowered by the Constitution to regulate federal elections without oversight from state courts, which is known as the independent state legislature doctrine. On November 4, 2021, the North Carolina General Assembly adopted a new congressional voting map based on 2020 Census data. The legislature, at that time, was controlled by the Republican Party. In the case Harper v. Hall (2022), a group of Democratic Party-affiliated voters and nonprofit organizations challenged the map in state court, alleging that the new map was a partisan gerrymander that violated the state constitution.[27] On February 14, 2022, the North Carolina Supreme Court ruled that the state could not use the map in the 2022 elections and remanded the case to the trial court for further proceedings. The trial court adopted a new congressional map drawn by three court-appointed experts. The United States Supreme Court affirmed the North Carolina Supreme Court's original decision in Moore v. Harper that the state's congressional district map violated state law. In a 6-3 decision, Chief Justice John Roberts wrote that the "Elections Clause does not vest exclusive and independent authority in state legislatures to set the rules regarding federal elections.[113]

Merrill v. Milligan (2023)

- See also: Merrill v. Milligan

At issue in Merrill v. Milligan, was the constitutionality of Alabama's 2021 redistricting plan and whether it violated Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act. A group of Alabama voters and organizations sued Secretary of State John Merrill (R) and the House and Senate redistricting chairmen, Rep. Chris Pringle (R) and Sen. Jim McClendon (R). Plaintiffs alleged the congressional map enacted on Nov. 4, 2021, by Gov. Kay Ivey (R) unfairly distributed Black voters. The plaintiffs asked the lower court to invalidate the enacted congressional map and order a new map with instructions to include a second majority-Black district. The court ruled 5-4, affirming the lower court opinion that the plaintiffs showed a reasonable likelihood of success concerning their claim that Alabama's redistricting map violated Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act.[114]

Gill v. Whitford (2018)

- See also: Gill v. Whitford

In Gill v. Whitford, decided on June 18, 2018, the Supreme Court of the United States ruled that the plaintiffs—12 Wisconsin Democrats who alleged that Wisconsin's state legislative district plan had been subject to an unconstitutional gerrymander in violation of the First and Fourteenth Amendments—had failed to demonstrate standing under Article III of the United States Constitution to bring a complaint. The court's opinion, penned by Chief Justice John Roberts, did not address the broader question of whether partisan gerrymandering claims are justiciable and remanded the case to the district court for further proceedings. Roberts was joined in the majority opinion by Associate Justices Anthony Kennedy, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Stephen Breyer, Samuel Alito, Sonia Sotomayor, and Elena Kagan. Kagan penned a concurring opinion joined by Ginsburg, Breyer, and Sotomayor. Associate Justice Clarence Thomas penned an opinion that concurred in part with the majority opinion and in the judgment, joined by Associate Justice Neil Gorsuch.[30]

Cooper v. Harris (2017)

- See also: Cooper v. Harris

In Cooper v. Harris, decided on May 22, 2017, the Supreme Court of the United States affirmed the judgment of the United States District Court for the Middle District of North Carolina, finding that two of North Carolina's congressional districts, the boundaries of which had been set following the 2010 United States Census, had been subject to an illegal racial gerrymander in violation of Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act. Justice Elena Kagan delivered the court's majority opinion, which was joined by Justices Clarence Thomas, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Stephen Breyer, and Sonia Sotomayor (Thomas also filed a separate concurring opinion). In the court's majority opinion, Kagan described the two-part analysis utilized by the high court when plaintiffs allege racial gerrymandering as follows: "First, the plaintiff must prove that 'race was the predominant factor motivating the legislature's decision to place a significant number of voters within or without a particular district.' ... Second, if racial considerations predominated over others, the design of the district must withstand strict scrutiny. The burden shifts to the State to prove that its race-based sorting of voters serves a 'compelling interest' and is 'narrowly tailored' to that end." In regard to the first part of the aforementioned analysis, Kagan went on to note that "a plaintiff succeeds at this stage even if the evidence reveals that a legislature elevated race to the predominant criterion in order to advance other goals, including political ones." Justice Samuel Alito delivered an opinion that concurred in part and dissented in part with the majority opinion. This opinion was joined by Chief Justice John Roberts and Justice Anthony Kennedy.[115][116][33]

Evenwel v. Abbott (2016)

- See also: Evenwel v. Abbott

Evenwel v. Abbott was a case decided by the Supreme Court of the United States in 2016. At issue was the constitutionality of state legislative districts in Texas. The plaintiffs, Sue Evenwel and Edward Pfenninger, argued that district populations ought to take into account only the number of registered or eligible voters residing within those districts as opposed to total population counts, which are generally used for redistricting purposes. Total population tallies include non-voting residents, such as immigrants residing in the country without legal permission, prisoners, and children. The plaintiffs alleged that this tabulation method dilutes the voting power of citizens residing in districts that are home to smaller concentrations of non-voting residents. The court ruled 8-0 on April 4, 2016, that a state or locality can use total population counts for redistricting purposes. The majority opinion was penned by Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg.[34][35][36][37]

Harris v. Arizona Independent Redistricting Commission (2016)

Harris v. Arizona Independent Redistricting Commission was a case decided by the Supreme Court of the United States in 2016. At issue was the constitutionality of state legislative districts that were created by the commission in 2012. The plaintiffs, a group of Republican voters, alleged that "the commission diluted or inflated the votes of almost two million Arizona citizens when the commission intentionally and systematically overpopulated 16 Republican districts while under-populating 11 Democrat districts." This, the plaintiffs argued, constituted a partisan gerrymander. The plaintiffs claimed that the commission placed a disproportionately large number of non-minority voters in districts dominated by Republicans; meanwhile, the commission allegedly placed many minority voters in smaller districts that tended to vote Democratic. As a result, the plaintiffs argued, more voters overall were placed in districts favoring Republicans than in those favoring Democrats, thereby diluting the votes of citizens in the Republican-dominated districts. The defendants countered that the population deviations resulted from legally defensible efforts to comply with the Voting Rights Act and obtain approval from the United States Department of Justice. At the time of redistricting, certain states were required to obtain preclearance from the U.S. Department of Justice before adopting redistricting plans or making other changes to their election laws—a requirement struck down by the United States Supreme Court in Shelby County v. Holder (2013). On April 20, 2016, the court ruled unanimously that the plaintiffs had failed to prove that a partisan gerrymander had taken place. Instead, the court found that the commission had acted in good faith to comply with the Voting Rights Act. The court's majority opinion was penned by Justice Stephen Breyer.[38][39][40]

Arizona State Legislature v. Arizona Independent Redistricting Commission (2015)