Pension reform: San Jose and San Diego voters weigh in

This article may not adhere to Ballotpedia’s current neutrality policies.

Pension reform: San Jose and San Diego Voters Weigh in

Download a free .pdf version of the report here.

By Brittany Clingen

October 15, 2013

One doesn’t need to know the intricacies of Detroit’s bankruptcy filing – the largest municipal bankruptcy to date – to know the city is in shambles.[1] Over 2,000 miles away in California, San Jose seems a far cry from the country’s formerly prosperous automotive capitol. The darling of Silicon Valley, San Jose is a big city with a small town feel and has become known for its affluence and low crime statistics. Though outward appearances suggest otherwise, these two cities have a lot in common.

Throughout the past several years, San Jose’s soaring pension costs were driving city leaders to cut services and employees. As payments to the pension fund began eating away at San Jose’s budget, the city crept ever closer to bankruptcy. Another of California’s largest cities, San Diego, was experiencing a similar problem. However, both these cities took a significant step on the road to solvency on June 5, 2012 when voters overwhelmingly approved sweeping pension reforms via the local ballot.

These two measures - San Jose’s Measure B and San Diego's Proposition B - were each placed on the ballot in different ways, but their goal was the same: to enact laws that would allow the cities to rein in skyrocketing pension costs and decrease unfunded pension liabilities in order to avoid cutting services, laying off workers and potentially filing for bankruptcy. With countless other cities across the country facing similarly grim pension crises, these two groundbreaking measures may well serve as examples for other cities that will need to choose between reform or bankruptcy.

San Jose Measure B

In August 2011, San Jose police spokesman Jose Garcia announced that, due to staffing shortages, the department would be categorizing noise complaints, burglar alarms and car crashes in which no one was injured as "non-response" incidents, meaning officers would not be sent to the scene. Garcia said, "To avoid frustration on the community's part, we'd just rather say look, these are the type of calls we will not be responding to because of the staffing levels."[2] In the month prior to Garcia's announcement, 66 police officers were laid off due to San Jose's severe budget deficit. San Jose Mayor Chuck Reed coined a specific term for the predicament the city was facing: service-level insolvency.[3]

After interviewing Mayor Reed for his November 2011 article in Vanity Fair - an article that later became an excerpt in his best-selling book, “Boomerang: Travels in the New Third World” - Michael Lewis wrote, "Service-level insolvency means that the expensive community center that has been built and named cannot be opened. It means closing libraries three days a week. It isn’t financial bankruptcy; it’s cultural bankruptcy."[4] For the citizens of San Jose - who were indeed coping with each of the deficiencies Lewis listed - after losing the assurance police would respond to their burglar alarms, it became a far more important issue than simply that of "culture."

Path to insolvency

"San Jose has the highest per capita income of any city in the United States, after New York. It has the highest credit rating of any city in California with a population over 250,000. It is one of the few cities in America with a triple-A rating from Moody’s and Standard & Poor’s, but only because its bondholders have the power to compel the city to levy a tax on property owners to pay off the bonds. The city itself is not all that far from being bankrupt," wrote Lewis.[4]

San Jose's financial woes materialized primarily due to the ever-growing amounts of money the city owes its employees, both current and former - amounts of money that are largely unfunded. San Jose's annual pension payments skyrocketed from $73 million in 2001 to $245 million in 2012, which is equal to 27 percent of its general fund budget.[5]

San Jose city councilmember Pete Constant, a former police officer, does not shy away from the fact that, at the time of Measure B's passage, he was the sole Republican on a council full of Democrats in a liberal city located in a very blue state. However, he and most of his fellow councilmembers, along with Democratic Mayor Reed, agreed on at least one thing: the pension system had to be reformed in order to save the city.

"The city of San Jose over the years has had a situation where, in the good years, as the city was growing and the economy was doing well, you had increasing pay for the employees, and in the years when we weren't doing so well financially, instead of giving pay raises during that time period, they would give increases to benefits,” said Constant. “In a relatively short period of time, our pension benefit was increased from 75% to 80% and then to 85% and then to 90%, in the case of public safety, and that was done all within a decade period."[6]

The increases were not just applied to future benefits but were implemented and applied retroactively for all members in the plan. In 1986, the unions struck a deal with the city while negotiating for enhanced health benefits for employees. In exchange for employees covering half the cost of retiree healthcare, they received full family coverage for life with zero co-payments. This was applied to all past, present and future employees.[6]

In 2006, when Constant took office, the city council realized, largely due to modifications of GASB (Governmental Accounting Standards Board) accounting standards, that although the original agreement was to split costs 50/50 between the employees and the city, in reality, only about 7 percent of the obligation had been funded. "We had gone an entire generation of employees who were supposed to be paying for a benefit that we [the city] are ultimately contracted and obligated to give but not really paying into it," said Constant.[6]

Path to the ballot

Constant chaired a task force which embodied city councilmembers, citizens and union members in order to discuss ways in which the city could move forward and tackle the crisis. First, a separate measure had to be put on the ballot that would eliminate the city charter's minimum pension requirement for future employees; voters passed this measure overwhelmingly. Then, a series of negotiations began between the city and its unions.[6]

Very little progress was made during the six plus months of negotiations with the unions. "Unfortunately, nobody really made any substantial effort to negotiate. That was very frustrating for us,” said Constant. “We had meeting after meeting after meeting that was canceled, meetings where we would go and there would be no productive discussions. So that's when we decided to move forward with a ballot measure.”[6]

The city council determined that the best plan of action was to craft a comprehensive pension reform ballot measure that would address everything from benefit structure, to cost of living adjustment (COLA) increases in retirements, to retiree health contributions and disability retirements.[6]

Though the city council approved the measure 8 to 3, everyone involved knew it would be a divisive issue throughout the city. People began gathering outside City Hall to protest Mayor Reed; for Constant, things became especially personal, with old friends and fellow police officers refusing to speak to him to this day.[6]

About Measure B

The final ballot language for Measure B was approved by the city council on March 6, 2012. Per the language and based on amendments made to the city’s charter, the measure would modify retirement benefits for city employees and retirees by “increasing employees’ contributions, establishing a voluntary reduced pension plan for current employees, establish pension cost and benefit limitations for new employees, modify disability retirement procedures, temporarily suspend retiree COLAs [cost of living adjustments] during emergencies, [and] require voter approval for increases in future pension benefits.”[7]

Election and aftermath

"The voters get it, they understand what needs to be done," said Reed.[5] With the exception of union sympathizers, the majority of the voters, regardless of party affiliation, wanted something done about the exorbitant pensions. Sixty-year-old San Jose resident Howard Delano said, "It's out of control. Nobody gives me a pension.”[8] On June 5, 2012, voters overwhelmingly approved Measure B 69.02 to 30.98 percent.

| Measure B | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Result | Votes | Percentage | ||

| 95,716 | 69.02% | |||

| No | 42,964 | 30.98% | ||

Less than 24 hours after the last vote was cast, the unions announced they would sue to prevent Measure B from being enacted. The coalition, led by the city's police union, argued that Measure B violated the vested pension rights of city employees, saying, "Those rights cannot be legislated away by defendant city of San Jose, or the voters because such rights are protected by the California Constitution and the parties' collective bargaining agreement."[9]

Measure B's supporters were prepared for the unions’ legal attack. "We expected lawsuits. This is California. Nothing important happens without litigation," said Reed. "We worked very hard with outside council to craft the measure in a way that followed California law and took advantage of our circumstance as a charter city and our charter that gives us some additional powers that other cities don't have and drafted a measure in a way that was the most defensible." The city argued that the burden of proving Measure B unconstitutional lies with the unions and that the unions "failed to proffer any testimony or other evidence."[10][9]

The lawsuit is currently ongoing, meaning the stipulations and adjustments laid out in Measure B have not yet been implemented.[9]

Three months after Measure B's landslide victory, the San Jose city council passed an ordinance, not tied to the approved measure, that laid out pension stipulations for future hires. The defined benefit plan states that pensions for non-safety workers will be two percent of an employee's final salary for each year worked, down from a rate of 2.5 percent. These pension payouts cannot exceed 65 percent of an employee's final salary. Additionally the minimum age requirement for full benefits was increased from 62 to 65.[11][9]

San Diego Proposition B

In January of 2006, a federal grand jury indicted five San Diego government officials and charged them with honest services mail fraud, wire fraud and conspiracy. Among those charged was Lawrence Grissom, the top executive for the San Diego City Retirement System (SDCRS). Charges were brought against the five individuals as a result of alterations made to the pension system in 2002. These changes, which were approved and adopted by the pension board, allowed the city to underfund the retirement system while giving city workers enhanced retirement benefits under separate labor contracts.[12]

The prosecutors on the case maintained that the five defendants conspired to pass the plan in order to receive enhanced benefits themselves. The charges were eventually dismissed[13], however this incident is just one among a litany of controversial, scandalous and legal problems that have plagued San Diego's pension system for the past two decades.

Path to insolvency

| “ | We knew that the crisis was so severe in San Diego that the public wanted pension reform. But those government employee unions owned the city council. Those city council members were not going to voluntarily reform pension benefits. So you're talking about a very small group of special interests - the government employee unions - controlling the city council and keeping in essence the rest of our city held hostage. So we knew we had to get this on the ballot. Put the issue in the hands of the people to actually get reform done.[14] | ” |

| —Carl DeMaio, former San Diego City Councilmember | ||

In 2009, the San Diego County Grand Jury released an investigative report that looked at why the city was facing such a dire financial situation. The report, which suggested filing for bankruptcy might well be the best course of action, stated, "One of the underlying causes of the current structural budget imbalance is the underfunding of the City’s pension obligation by previous City administrations." Until 1996, when the pension system was 92.3 percent funded, the city made payments to the San Diego City Employees' Retirement System (SDCERS) as prescribed by the SDCERS actuary. However, by June 2009, the pension fund was only 66.5 percent funded. Beginning in the mid-1990s, San Diego set itself on a course that soon spiraled out of control, leaving the city nearly broke and taxpayers on the hook for millions of dollars.[15]

In an attempt to balance the city's budget, the 1996 city council approved then-city manager Jack McGrory's proposal to increase employee benefits while underfunding the pension plan by $110 million over the course of 10 years. Encouraged by double-digit stock market returns in recent years, McGrory believed it was a perfectly viable budget-balancing option that would not put a burden on the robust pension fund.[16]

This perfect storm of underfunding the pension system while promising more and more to the city employees brought San Diego to the brink of bankruptcy multiple times and sent pension liabilities soaring from $43 million in 1999 to $231.2 million in 2012. Nearly 20 years after the city's pension debacle began - after credit downgrades, criminal investigations, scandals and diminished city services - San Diego's citizens finally decided enough was enough.[17]

Path to the ballot

Unlike San Jose's Measure B, Proposition B was a citizen-initiated ballot measure and was put on the ballot by the people of San Diego, as opposed to the city council. At the time, Carl DeMaio was a member of the city council and a candidate for mayor. Acting as a private citizen, he, along with then-mayor Jerry Sanders, was one of Prop B’s most fervent supporters, often spending hours in front of local stores attempting to get signatures for the measure.[18]

"The biggest challenge was just getting it on the ballot,” said DeMaio. “We knew that the crisis was so severe in San Diego that the public wanted pension reform. But those government employee unions owned the city council. Those city council members were not going to voluntarily reform pension benefits. So you're talking about a very small group of special interests - the government employee unions - controlling the city council and keeping in essence the rest of our city held hostage. So we knew we had to get this on the ballot. Put the issue in the hands of the people to actually get reform done.”[18]

Supporters of Prop B had to collect over 94,000 valid signatures from registered voters in order to put their initiative on the ballot. This proved to be no easy task. Opponents of Prop B raised significant money from outside groups - with a large portion coming from pro-union interests in Sacramento - and ran radio ads stating that people who signed petitions in support of Prop B would get their identity stolen.[18]

The unions also attempted to taint the Prop B petitions with fraudulent signatures. In late July - approximately two months out from the October 14, 2011 signature due date - Prop B supporters detected approximately 20,000 fraudulent signatures on their petitions. In petition drives, for every one duplicate signature found in a random sample, the campaign is penalized approximately 1,000 signatures in the overall count. Two previous ballot measures that San Diego unions opposed suffered from a massive number of duplicate signatures, leading some, including DeMaio, to believe that the unions were running a deliberate campaign to flood the petitions with duplicate and fraudulent signatures, in hopes of keeping Prop B from ever reaching the ballot.[18]

In order to combat the fraudulent signature issue, the Prop B campaign verified 100 percent of the petition drive signatures. This required conducting a three-tiered test which:[18]

- 1) Confirmed the name listed was not a duplicate

- 2) Confirmed the person was a registered voter in San Diego

- 3) Confirmed the signature was a match with the one the registrar had on file.

Though this technique cost the Prop B campaign significant time, money and resources, it ensured that the measure made it onto the ballot.

Unions hired "blockers" to confront and harass signature gatherers who set up camp in front of stores and other public places. When signature gatherers reported to T.J. Zane, president of the San Diego Lincoln Club and one of the official sponsors of Prop B, that they were being harassed, he hired a private investigator to film exchanges between signature gatherers and union activists.[18][19]

“The blocking was very effective because in our signature drive we saw our tallies of signatures drop significantly. People were refusing to carry the petition because they were afraid that they'd be harassed. So we had to get creative in how we got our signatures,” said DeMaio. Supporters recruited volunteers, mailed petitions to individuals so they could collect signatures in their neighborhoods and workplaces and employed a "massive door-to-door walking program," which is how most of the remaining signatures were collected in the final months leading up to the signature deadline.[18]

About Proposition B

Like Measure B, San Diego’s Prop B sought to curb pension costs via several different changes to the city charter. These changes included giving new city workers a 401(k)-style retirement plan with a city match instead of a guaranteed pension; maxing out the guaranteed pensions for newly-hired public safety workers at 80 percent, as opposed to the standard 90 percent; capping the city’s payroll for five years at its 2011 pay rate, which was less than $600 million annually; and striking a provision from the charter that required a majority vote of all city employees to approve any changes to retirement benefits.[20]

Election and aftermath

Voters approved Prop B by a wide margin of 65.81 percent to 32.19 percent.

| Proposition B | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Result | Votes | Percentage | ||

| 154,216 | 65.81% | |||

| No | 80,126 | 34.19% | ||

Like in San Jose, challenges followed the vote. The Public Employment Relations Board (PERB) filed injunctions against Prop B three separate times - once before it was on the ballot and twice after its approval. Each time, City Attorney Jan Goldsmith argued against PERB's injunctions and won. "We beat PERB. They lost. They were unable to stop it. That was the first time PERB lost an injunction motion in its history, from what I understand," said Goldsmith.[21]

PERB's attacks may continue, but Goldsmith asserted that if the unions wanted to keep fighting the voters' decision, the city was more than prepared to take them on in court. Goldsmith couldn't help but smile when discussing Prop B - which he believes is smart, fair reform . "Today,” he beamed, “I can say Proposition B is being implemented in accordance with its terms."[21]

Looking forward

"I did a calculation of cost per public employee. We're not as bad as Greece, I don't think,” said Reed in his 2011 interview with Lewis about San Jose's financial woes. Back in 2011, Reed calculated that by 2014, San Jose, with a population of over 980,000 would be able to afford approximately 1,600 public workers to keep the city clean, safe and functioning. "There is no way to run a city with that level of staffing. You start to ask: What is a city? Why do we bother to live together?" Reed said to Lewis.[4]

The first piece of the pension puzzle that must be altered is that of governance. "In most cases, pension systems or boards are dominated, not surprisingly, by beneficiaries, by the public employee union members," says Joe Nation, a former Democratic California State Assemblyman who currently teaches several policy courses at Stanford. He was also commissioned to do research on California's public employee benefits crisis. "They may not have the best long-term perspective or they might have conflicting interests, and so, in the end, you end up with decisions on a board that may not make the best long-term decisions even for its members and for beneficiaries. And you also have members, trustees who just don't have the background that they should."[22]

Both Measure B and Proposition B were bipartisan efforts that served as public referendums on pension reform. As supporters of Measure B and Prop B can attest to, enacting pension reform is no easy task, with hundreds of hours and people and millions of dollars being poured into the effort.

“The key issue when you are dealing with pension reform is whether you are affecting vested rights, vested benefits; vested meaning the government can't take it away from you,” said Goldsmith. He suggested reformers focus on things that can be changed, such as benefits for new hires and employees’ salaries.[21]

DeMaio stressed the importance of seeking outside legal counsel. “I always encourage elected officials, taxpayer groups to seek outside council. Really take a look at your options before you just blindly accept the proclamations of government attorneys and labor unions,” he said.[18]

Pension reform will always be an incendiary topic, one which is likely to elicit strong emotional responses from people on both sides of the issue. “I think it’s important that when people are crafting solutions to solve a problem that - fundamental fairness is important to the voters. […] The voters understand it’s a big problem, but they also want to be fair,” said Mayor Reed.[10]

Measure B and Prop B were steps in the right direction. Nation said, “[local governments] will have to move towards something where the risk is shifted to the employees, as opposed to the risk being borne by the city or, implicitly, by taxpayers. You can’t expect to maintain a system that offers too much in the end, that provides benefits that simply aren’t sustainable. Because they’re not sustainable, that’s the bottom line.”[22]

See also

- Free digital download of Pension reform: San Jose and San Diego voters weigh in

- Local Ballot Initiatives: How citizens change laws with clipboards, conversations, and campaigns

- San Diego Pension Reform Initiative, Proposition B (June 2012)

- San Jose Pension Reform, Measure B (June 2012)

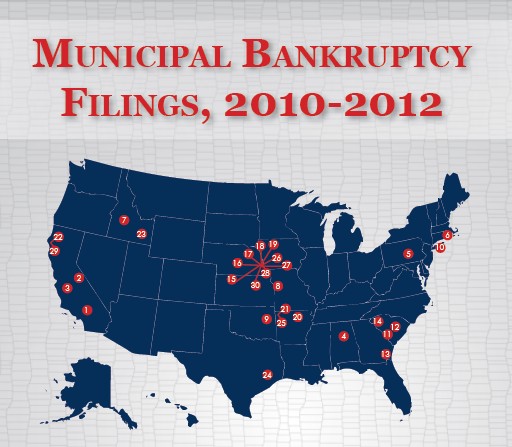

- Pension Hotspots Report

Footnotes

- ↑ State Budget Solutions, "Municipal Bankruptcy: An Overview for Local Officials," February 26, 2013

- ↑ CBC San Francisco, "Cash-Strapped San Jose Police Won’t Respond To Low-Priority Calls," August 17, 2011

- ↑ Reuters, "California cities scramble to avert insolvency," March 19, 2012

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Vanity Fair, "California and Bust," November 2011

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Business Insider, "San Diego And San Jose Approve Pension Cuts In A Landslide Vote," June 6, 2012

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 Ballotpedia interview with Councilmember Pete Constant, June 11, 2013

- ↑ San Jose Fiscal Reforms, "About Measure B," accessed October 9, 2013

- ↑ MercuryNews.com, "All precincts counted: San Jose passes pension reform," June 5, 2012

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 Reuters, "San Jose and unions make final argument in battle over pension cuts," September 10, 2013

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Ballotpedia interview with Mayor Chuck Reed, June 13, 2013

- ↑ Reason Foundation, "Analysis: San Diego, San Jose lead the way in local pension reform," May 6, 2013

- ↑ U-T San Diego, "Experts eye gap between pension case indictments," October 20, 2008

- ↑ San Diego Reader, "Judge Dumps Criminal Pension Charges," April 7, 2010

- ↑ Note: This text is quoted verbatim from the original source. Any inconsistencies are attributable to the original source.

- ↑ County of San Diego, "San Diego City's Financial Crisis: The Past, Present, and Future," accessed October 11, 2013

- ↑ UT San Diego, "City has a deal, but will pension trustees buy it?" June 21, 1996

- ↑ KPBS, "San Diego Voters Approve Cuts To City Pensions," June 6, 2012

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 18.4 18.5 18.6 18.7 Ballotpedia interview with former Councilmember Carl DeMaio, August 6, 2013

- ↑ U-T San Diego, "Pension battle pitched over signature-gathering," June 26, 2011

- ↑ City of San Diego, "Proposition B," accessed October 10, 2013

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 Ballotpedia interview with City Attorney Jan Goldsmith, August 8, 2013

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Ballotpedia interview with Joe Nation, September 25, 2013