AUTHOR’S NOTE: Kenai Peninsula citizens voted in 1963 to create a second-class governing entity called the Kenai Peninsula Borough, which was incorporated at the beginning of 1964. They also selected the borough’s first executive, Borough Chairman Harold Pomeroy. Then it was time to decide where the new borough’s administrative seat was to be.

After the Kenai Peninsula Borough was incorporated on Jan. 1, 1964, assembly members knew that they had to select a seat of government. They also knew that such a selection might be difficult.

It didn’t take long for the sparks to fly.

Battle for the seat of power

On Jan. 10, near the end of a page-one article in the Cheechako News, Kenai mayor James G. “Bud” Dye suggested that, despite its initial activities in Soldotna, the borough could move to Kenai and use a classroom in the Kenai School as a headquarters until the end of present school term, when a suitable new location, preferably still in Kenai, could be found.

A week later, at the behest of the Greater Soldotna Chamber of Commerce, Beulah Grange submitted to the newspaper a long and detailed list of all the services available in the Soldotna area. The Cheechako printed the list on page 11 under the headline “Soldotna to Make Bid for Borough Seat.” The dozens of services were listed under eight main headings: housing and food; consumer services; religion, entertainment and education; transportation; business and professional services; medical services; government institutions; and utilities.

The very next day in the Kenai School, at a special meeting of the borough assembly, Kenai countered.

When Agenda Item #10, “Location of Borough Seat,” was called, Assemblyman Dick Morgan, representing the Kenai City Council, announced that space was available in the brand-new Kenai Central High School until the end of August, when the facility was scheduled to open to students for the first time.

Morgan added that some room might soon be available at the Kenai Airport, and then he made a motion to introduce a resolution to bring the borough seat to Kenai. No one seconded his motion.

Instead, Assemblyman Morris Coursen made a motion to introduce a resolution to locate the borough seat in Soldotna. After Coursen’s motion was seconded, a vote was taken and the motion passed 6-1. Only Morgan dissented.

In retaliation, Morgan requested that Coursen’s resolution be made temporary until the borough completed its first master plan, and his request was granted. Consequently, no borough headquarters could be constructed until this “temporary” solution was made permanent; therefore, the question of borough seat location remained unresolved.

Unresolved or not, however, the banner headline on page one of the next edition of the Cheechako blared “BOROUGH SEAT CHOSEN.”

The assembly had agreed unanimously to accept an offer from Jack and Dolly Farnsworth for the free use of a single 10×10-foot room in the Farnsworth Building, located near the intersection of the Spur and Sterling highways, where Dolly ran her Soldotna Bookkeeping business. The arrangement seemed adequate, especially in light of the fact that the borough initially had only one employee, Chairman Harold Pomeroy.

Of course, government has a tendency to grow. Soon a clerk was hired, and then an assessor and three appraisers, and so on.

By April 1965, the borough was occupying 818 square feet in the Farnsworth Building, and the owners were now charging a monthly rate for the space — 22 cents per square foot (including utilities). In mid-May, Chairman Pomeroy predicted that by July the borough would require about 1,600 square feet of space for all its employees and materials.

On June 1, the City of Kenai tried again to come to the rescue. The city offered to lease the borough space for the dirt-cheap price of 10 cents per square foot — based upon a long-term lease agreement, preferably for something in the 30-year range — in the newly approved Kenai Airport terminal. Kenai Mayor Dye estimated that the space would be available to the borough by Jan. 1, 1966.

From the Soldotna Chamber, Burton Carver offered a rebuttal of sorts. Carver told the assembly that the borough seat had already been placed in Soldotna after a lengthy discussion and a vote of assembly members; that decision, he asserted, should not be rashly altered. Carver added that the Soldotna location was the most central for the most peninsula residents and, consequently, the most economical.

Most of the assembly concurred and stated that any change should occur — if at all — only after more public hearings. Assembly members voted 5-2 to keep the borough headquarters right where it was, and then, later in the same meeting, voted unanimously to lay the issue of a permanent borough seat to rest once and for all with a borough-wide election on Oct. 5.

Going to a vote

Resolution #52 was drafted to request applications for the borough seat referendum. Communities interested had to have an application in to the borough office by Sept. 10 in order to be placed on the general election ballot.

As the deadline approached, three cities filed applications — Seward first, then Soldotna and Kenai. After that trio, a pair of surprises arose.

First, the assembly received a letter signed by two individuals — probably homesteader Paul Costa and surveyor F.J. “Francis” Malone — in the Gruening Subdivision north of Kenai, asking that the community of Gruening be considered for application on the ballot. This request left assembly members somewhat befuddled as they questioned whether a letter signed by only two people could be the equivalent of an application from a city or a community organization or group.

Tiny Gruening, more a dream than an actual community, had been named after U.S. Senator Ernest Gruening and was the brainchild of Costa and Malone, with financial support from Ron Mika. At its peak, it comprised fewer than a half-dozen buildings in a cleared area near the intersection of the North Road and Lamplight Road.

About a week after the arrival of the Gruening letter, Kenai city manager Bill Harrison drove north to speak at a meeting of the North Kenai Community Club and urged Gruening supporters to support Kenai’s bid, instead. The Gruening bid, he said, might disrupt the “harmony” and the “unity” between Kenai and North Kenai, and the community club members agreed. The Gruening request was withdrawn.

The second surprise entry arrived on the last day of the application process: Clam Gulch, supported by the Tustumena Chamber of Commerce, applied to become the borough seat.

Chamber president, Arlyn “Speedy” Thomack, reminded the public that the original Kenai Peninsula Borough Study Group had recommended that the borough seat be in the Tustumena area. At its Sept. 14 meeting, the assembly announced that all four communities would go on the ballot. The winning site would be chosen by plurality.

During the next 19 days, the rhetoric and the action intensified without getting ugly. In the final week, the Tustumena Chamber met to listen to promotional presentations from representatives of both Kenai and Soldotna, and then decided to drop Clam Gulch from the race without officially endorsing any other community.

In the Friday, Oct. 1 edition of the Cheechako, however, the Tustumena explanation seemed to favor Soldotna. “CLAM GULCH STEPS OUT” read the all-caps headline atop page one, and chamber president Thomack stated that Tustumena was “in favor of a centrally located place on the Sterling Highway.”

In the same newspaper, Kenai ran a full-page ad promoting a dozen good reasons why it should be selected as borough seat. Kenai emphasized that it was in the heart of the oil industry, had fine air-transport facilities, was the headquarters for a high-volume recording district, and was adjacent to “the best dock accommodations on Cook Inlet, namely Arness Terminal.”

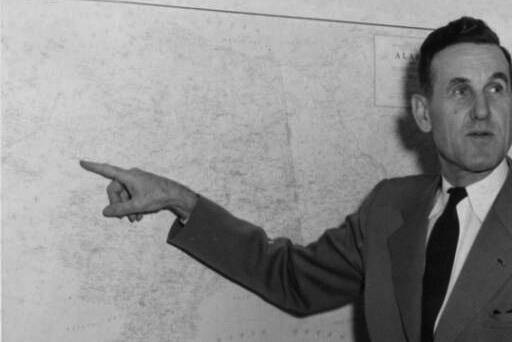

Soldotna ran its own full-page ad, featuring a large map illustrating that it was the crossroads of the peninsula. It called itself “The Hub” and reminded readers that moving the borough seat out of Soldotna would involve more and unnecessary expense.

Not to be outdone, Seward ran its own ad spanning two full pages and providing 15 good reasons why it deserved to be the borough seat. Seward emphasized that it had office space already available, in addition to an “All-America” city designation, and many modern conveniences.

The Cheechako, which in those days rarely ran an issue larger than 16 pages, on this day filled 24, mostly with advertising and election-related stories. One of its most important stories shared the front page with the Clam Gulch article; it was entitled “Homer Endorses Soldotna,” and it made official the stance of the southern peninsula.

On election day, Tuesday, Oct. 5, voters came out in record numbers.

Because Clam Gulch had dropped out so near the election, there had been no time to reprint the ballots; consequently, Clam Gulch received 16 votes (0.5 percent). Kenai finished third, barely, with 805 votes (25.7 percent), while Seward finished in second with 809 votes (25.8 percent). And Soldotna won easily with 1,499 votes (47.9 percent).

Kenai had received nearly all of its support from Kenai and Nikiski area voters, while Seward’s support was limited to its two precincts and Moose Pass. Soldotna, on the other hand, received the lion’s share of the votes in nearly every other precinct.

In his editorial in the Oct. 8 edition of the Cheechako, publisher Loren Stewart offered the following words as closure: “The election is over. The most controversial borough issue — the location of the borough seat — has been conclusively decided. The contenders, Seward and Kenai, have accepted this decision and announced their desire to now get on with the serious business of building a good borough government.

“All three cities,” he continued, “are to be complimented on carrying on honest, straightforward, mature campaigns for the borough seat. Campaigns which left little or no ill will and bitterness in their wake. Campaigns which in fact drew the several communities of the peninsula closer together. As far as these cities are concerned, the election is over.”