The Taney Court

| SCOTUS |

|---|

|

| Cases by term |

| Judgeships |

| Posts: 9 |

| Judges: 9 |

| Judges |

| Chief: John Roberts |

| Active: Samuel Alito, Amy Coney Barrett, Neil Gorsuch, Ketanji Brown Jackson, Elena Kagan, Brett Kavanaugh, John Roberts, Sonia Sotomayor, Clarence Thomas |

The Taney Court lasted from March 1836 to October 1864, during the presidencies of Andrew Jackson (D), Martin Van Buren (D), William Henry Harrison (Whig), John Tyler (Whig), Zachary Taylor (Whig), Millard Fillmore (Whig), Franklin Pierce (D), James Buchanan, and Abraham Lincoln (R).

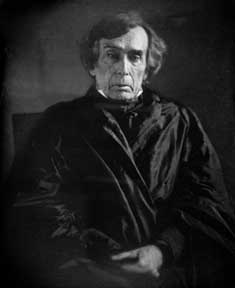

Roger Brooke Taney was nominated as the fifth Supreme Court Chief Justice by President Andrew Jackson (D) on December 28, 1835. Taney was later confirmed by the Senate and served from March 15, 1836, to October 12, 1864. Previously, he had been nominated as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court in 1835, but that nomination was indefinitely postponed.[1]

Associate justices

The justices in this table served during the Taney Court.

Major cases

States have the right to protect their citizens (1837)

- See also: Supreme Court of the United States (Mayor of New York v. Miln, 36 U.S. 102)

- See also: Supreme Court of the United States (Mayor of New York v. Miln, 36 U.S. 102)

Miln was the master of the ship the Emily that was docking in New York. When he refused to comply with the state law requiring him to provide a list of passengers and to use security to prevent them from becoming public charges, New York City sought to penalize him. Despite the Commerce Clause, the Supreme Court affirmed the previous decision and ruled in favor of New York, saying that it had the right to protect its citizens.[2]

Briscoe v. Bank of Commonwealth of Kentucky (1837)

- See also: Supreme Court of the United States (Briscoe v. Bank of Commonwealth of Kentucky, 36 U.S. 1837)

- See also: Supreme Court of the United States (Briscoe v. Bank of Commonwealth of Kentucky, 36 U.S. 1837)

The Bank of Commonwealth of Kentucky gave Briscoe bank notes in exchange for a promissory note. Briscoe did not repay the note, and the bank sued him. Briscoe alleged that the bank violated the Constitution, citing the Article I prohibition of states to issue lines of credit. On February 11, 1837, the Supreme Court found in favor of the Bank of Kentucky, holding that the bank notes were issued on the bank's line of credit.[3]

Community interest weighed over private property (1837)

- See also: Supreme Court (Proprietors of Charles River Bridge v. Proprietors of Warren Bridge, 36 U.S. 420)

- See also: Supreme Court (Proprietors of Charles River Bridge v. Proprietors of Warren Bridge, 36 U.S. 420)

In 1828, the Massachusetts legislature wanted to build a bridge and established the Warren Bridge Company to do so. Since it would compete for traffic and tolls with the nearby Charles River Bridge, the Charles River Bridge filed suit, arguing that the legislature defaulted on its initial contract.[4] On February 14, 1837, the Supreme Court decided 5-2 in favor of the Warren Bridge, saying that the state never entered into an agreement restricting the construction of another bridge nearby the Charles River Bridge.[5] This marked a shift from national rights that were emphasized in the Marshall Court to state rights in the Taney Court.[4]

Prigg v. Pennsylvania (1842)

- See also: Supreme Court (Prigg v. Pennsylvania, 41 U.S. 539)

- See also: Supreme Court (Prigg v. Pennsylvania, 41 U.S. 539)

In 1788 and 1826, Pennsylvania enacted state law prohibiting individuals from removing Black people from the state in order to enslave them. In 1832, Margaret Morgan, a Black woman, moved from Maryland to Pennsylvania. Morgan had been informally emancipated by slaveowner John Ashmore. Ashmore's heirs sought to re-enslave Morgan and sent Edward Prigg to capture her. Prigg did so. Prigg was convicted in Pennsylvania court for violating state law. On appeal to the Supreme Court, Prigg argued that the state law violated federal law, including the Fugitive Slave Law of 1793. On March 1, 1842, the Supreme Court held that the Pennsylvania laws were unconstitutional. Justice Joseph Story delivered the opinion of the court, writing that state laws dictating the recapture of slaves from free states only needed to be enforced by federal officials and not state magistrates.[6]

Congress and the President have the right to address creation of republican governments (1849)

- See also: Supreme Court of the United States (Luther v. Borden, 48 U.S. 1)

- See also: Supreme Court of the United States (Luther v. Borden, 48 U.S. 1)

In 1841, Rhode Island was using a system of government established by a royal charter in 1663 that limited suffrage and did not provide for amendments. Groups held a popular convention to draft a new constitution and elect a new government. The existing government declared martial law in order to stop the protests. Martin Luther sued the state government, challenging that it was not a republican form of government. On January 3, 1849, the Supreme Court ruled Congress and the President were empowered to address issues of creating republican forms of government and controlling domestic violence. Roger B. Taney authored the decision, with Levi Woodbury dissenting.[7]

Dred Scott v. Sandford (1857)

- See also: Supreme Court of the United States (Dred Scott v. Sandford, US 54729-23-6832)

- See also: Supreme Court of the United States (Dred Scott v. Sandford, US 54729-23-6832)

Dred Scott was enslaved in Missouri by Sandford. From 1833 to 1843, he lived in the free state Illinois and in the Louisiana Territory, where slavery was forbidden by the Missouri Compromise of 1820. Upon his return to Missouri, Scott sued for his freedom in state court on the basis that he had lived in free territory. The court ruled against his claim. Scott then filed suit in federal court for his freedom. Sandford argued that no Black person or descendant of enslaved persons could be a U.S. citizen. On March 6, 1857, the Supreme Court ruled in Sandford's favor by a 7-2 vote. Taney delivered the majority opinion, stating that Black people with ancestors who had been enslaved, whether they themselves were enslaved or free, could not be U.S. citizens and as a result, Scott did not have standing to sue for his freedom in federal court. Taney also concluded that the Missouri Compromise of 1820 was unconstitutional, and that enslaved people were property under the Fifth Amendment.[8][9][10]

Prisoners of the federal government cannot be released by the state (1859)

- See also: Supreme Court of the United States (Ableman v. Booth, 62 U.S. 506)

- See also: Supreme Court of the United States (Ableman v. Booth, 62 U.S. 506)

Joshua Glover, an enslaved person, had run away in order to escape his captivity. He was detained by the U.S. government in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Sherman Booth petitioned for his release in local court; the federal government did not accept the local judge's release order. Meanwhile, a group of individuals freed Glover. Booth was charged with violating the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 for allegedly helping Glover escape. Booth petitioned the Supreme Court of Wisconsin for release, and the court granted it. The U.S. government detained Booth again and he was convicted in the United States District Court for the District of Wisconsin. Booth petitioned the state supreme court for release again, arguing that the federal court lacked jurisdiction. He was released. The federal government appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court. On March 7, 1859, the court ruled unanimously that the Supreme Court of Wisconsin did not have the right to release Booth since he was a prisoner of the federal government.[11]

About the court

- See also: Supreme Court of the United States

The Supreme Court of the United States is the highest judicial body in the country and leads the judicial branch of the federal government. It is often referred to by the acronym SCOTUS.[12]

The Supreme Court consists of nine justices: the Chief Justice of the United States and eight Associate Justices. The justices are nominated by the president and confirmed with the "advice and consent" of the United States Senate per Article II of the United States Constitution. As federal judges, the justices serve during "good behavior," which means that justices have tenure for life unless they are removed by impeachment and subsequent conviction.[13]

On January 27, 2022, Justice Stephen Breyer officially announced he would retire at the start of the court's summer recess.[14][15] Breyer assumed senior status on June 30, 2022.[16] Ketanji Brown Jackson was confirmed to fill the vacancy by the Senate in a 53-47 vote on April 7, 2022.[17] Click here to read more.

The Supreme Court is the only court established by the United States Constitution (in Article III); all other federal courts are created by Congress.

The Supreme Court meets in Washington, D.C., in the United States Supreme Court building. The Supreme Court's yearly term begins on the first Monday in October and lasts until the first Monday in October the following year. The court generally releases the majority of its decisions in mid-June.[13]

Number of seats on the Supreme Court over time

- See also: History of the Supreme Court

| Number of Justices | Set by | Change |

|---|---|---|

| Chief Justice + 5 Associate Justices | Judiciary Act of 1789 | |

| Chief Justice + 4 Associate Justices | Judiciary Act of 1801 (later repealed) | |

| Chief Justice + 6 Associate Justices | Seventh Circuit Act of 1807 | |

| Chief Justice + 8 Associate Justices | Eighth and Ninth Circuits Act of 1837 | |

| Chief Justice + 9 Associate Justices | Tenth Circuit Act of 1863 | |

| Chief Justice + 6 Associate Justices | Judicial Circuits Act of 1866 | |

| Chief Justice + 8 Associate Justices | Judiciary Act of 1869 |

See also

External links

- Search Google News for this topic

- Supreme Court Historical Society, "The Taney Court"

- Supreme Court Historical Society, "Timeline of the Justices"

- Biography from the Federal Judicial Center

- U.S. Supreme Court

- SCOTUSblog

Footnotes

- ↑ Federal Judicial Center, "Taney, Roger Brooke," accessed March 14, 2022

- ↑ Oyez, Mayor of New York v. Miln, decided February 16, 1837

- ↑ Oyez, Briscoe v. Bank of Commonwealth of Kentucky, decided February 11, 1837

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 PBS, "Landmark Cases: Charles River Bridge v. Warren Bridge"

- ↑ Oyez, Proprietors of Charles River Bridge v. Proprietors of Warren Bridge, decided February 14, 1837

- ↑ Oyez, Prigg v. Pennsylvania, decided March 1, 1842

- ↑ Oyez, Luther v. Borden, decided January 3, 1849

- ↑ Missouri Government, “Missouri’s Dred Scott Case, 1846-1857"

- ↑ Our Documents, Dred Scott v. Sanford

- ↑ Oyez, Dred Scott v. Sandford, decided March 6, 1857

- ↑ Oyez, Ableman v. Booth, decided March 7, 1859

- ↑ The New York Times, "On Language' Potus and Flotus," October 12, 1997

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 SupremeCourt.gov, "A Brief Overview of the Supreme Court," accessed April 20, 2015

- ↑ United States Supreme Court, "Letter to President," January 27, 2022

- ↑ YouTube, "President Biden Delivers Remarks on the Retirement of Supreme Court Justice Stephen Breyer," January 27, 2022

- ↑ Federal Judicial Center, "Breyer, Stephen Gerald," accessed April 13, 2023

- ↑ Congress.gov, "PN1783 — Ketanji Brown Jackson — Supreme Court of the United States," accessed April 7, 2022

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Active justices |

Chief justice: Roberts | ||

| Senior justices | |||

| Former chief justices |

Burger • Chase • Ellsworth • Fuller • Hughes • Jay • Marshall • Rehnquist • Rutledge • Stone • Taft • Taney • Vinson • Waite • Warren • White | ||

| Former associate justices |

Baldwin • Barbour • Black • Blackmun • Blair • Blatchford • Bradley • Brandeis • Brennan • Brewer • Brown • Burton • Butler • Byrnes • Campbell • Cardozo • Catron • Chase • Clark • Clarke • Clifford • Curtis • Cushing • Daniel • Davis • Day • Douglas • Duvall • Field • Fortas • Frankfurter • Ginsburg • Goldberg • Gray • Grier • Harlan I • Harlan II • Holmes • Hunt • Iredell • H. Jackson • R. Jackson • T. Johnson • W. Johnson, Jr. • J. Lamar • L. Lamar • Livingston • Lurton • Marshall • Matthews • McKenna • McKinley • McLean • McReynolds • Miller • Minton • Moody • Moore • Murphy • Nelson • Paterson • Peckham • Pitney • Powell • Reed • Roberts • W. Rutledge • Sanford • Scalia • Shiras • Stevens • Stewart • Story • Strong • Sutherland • Swayne • Thompson • Todd • Trimble • Van Devanter • Washington • Wayne • B. White • Whittaker • Wilson • Woodbury • Woods | ||